Two years after the costliest and one of the strongest hurricanes to hit the United States, New Orleans’ pain is still fresh.

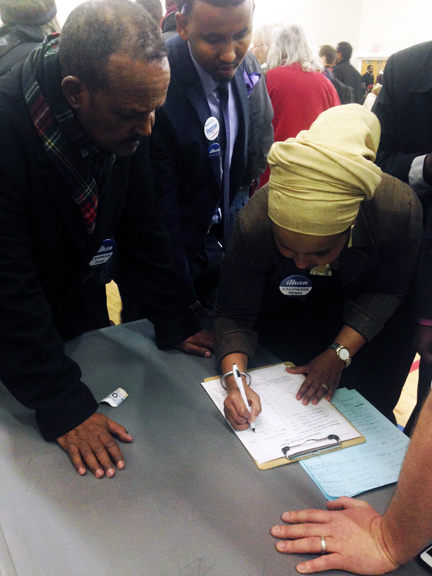

NEW ORLEANS – Nearly two hundred New Orleans residents and their supporters assembled on a Saturday morning along the Monticello Canal to do something their government had refused to do: build a levee.

The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), a community-based coalition fighting for the rights of low and moderate income families, organized the demonstration forming a “Human Levee for Human Rights” demanding residents’ right to equitable flood protection.

A reinforced levee and floodwall protects Jefferson Parish, a wealthier neighbor of Orleans Parish, from the Monticello Canal. Despite defenses reaching twelve feet above the ground on one side, the predominantly African-American working class neighborhood of Carrollton-Hollygrove bordering the Orleans Parish side, the canal stands unprotected. This disparity provides a shocking view into environmental injustices faced by numerous African American neighborhoods in New Orleans.

“This neighborhood has always flooded during heavy rains,” Joe Sherman, a longtime resident and ACORN neighborhood chair, told protesters as rain clouds loomed ominously over head. “Our community is left vulnerable while the state, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Water and Sewerage Board keep pointing fingers.”

Two years after Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc in New Orleans, the city’s most-affected resident feel that whatever rebuilding progress they have made is in danger because the government has done very little to protect them. Residents fear that should another disaster of Katrina’s magnitude happen, it would be more damaging. Katrina left at least 1,836 dead across the Gulf Coast, with 75 percent of those deaths occurring in New Orleans. A third of the city’s population, nearly 150,000 people, still hasn’t returned to the city.

Sherman, who worked for twenty years in the engineering department of the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans, explained how he and his neighbors have been fighting for years – even before Hurricane Katrina – for flood protection, but had been told their community was not a priority. During the New Orleans recovery planning process, residents set flood protection as a top priority, but planners determined it would not be addressed for five years or more in Carrollton-Hollygrove.

Since the Army Corps of Engineers took over New Orleans’ flood control system in 1965, residents said Carrollton-Hollygrove flooded eight different times. Floodwaters reached eight feet high in some homes after Hurricane Katrina. Making matters even worse, the current city drainage system pumps more water into the Monticello Canal than is pumped out, frequently forcing floodwaters over into this neighborhood during most major rain events.

“The risks increase for these residents because there is protection on one side, and no protection on the other,” said Stephen Bradberry, Louisiana ACORN head organizer and 2005 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award winner. “How can you say the community not at risk when you have protected one half of the community and not the other?”

Leftovers from the age of slavery”

Dr. Robert Bea, lead investigator on the National Science Foundation’s inquiry into New Orleans’ flood protection system, confirmed that placing a levee and floodwall on one side along the Monticello Canal but not the other had no grounding in science.

“It is perfect example of the disconnected incomplete nature of this flood protection system,” said Bea in a recent interview. “Much of what happened [there] during Katrina represents the leftovers from the age of slavery in the South.”

The Chicago Tribune in a revealed recent report that the $1.6 billion worth of work done by the Corps of Engineers since Hurricane Katrina has overwhelmingly benefited New Orleans’ wealthier white neighborhoods, continuing to leave African-American areas vulnerable.

Forming a human levee

To expose the inequity and garner attention to the dangers of inadequate protection that lower income residents face, demonstrators formed a human levee stretching over a third of a mile.

Participants included local residents, ACORN members from across the city, United Teachers of New Orleans and AFL-CIO members, as well as supporters from the Washington, DC-based RFK Memorial Center for Human Rights.

As protesters lined the Monticello Canal, Kerry Kennedy, daughter of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, told the crowd how African slaves 200 years ago in New Orleans were stacked one on top of another, forming a “human levee”, to protect white property from oncoming floodwaters.

Kennedy equated this to the current discriminatory flood protection system where predominantly black neighborhoods remain vulnerable while white communities receive increased protection. Such inequality makes it harder for African American families to return home, in violation of international human rights law, she said.

While some residents have not been able to return, many homes are showing signs of coming back. Lifetime Hollygrove resident Nyra Humphries is almost finished repairing her home. Looking at the Monticello Canal everyday, she could not help but worry that her months of hard work would be in vain.

"It’s hard to put so much time and money into my home when there’s no work done to prevent more flooding," Humphries said.

Also in attendance was a church group from Milwaukee that had been repairing homes in the Ninth Ward with ACORN but took a break to support to the protest.

"We thought it was important to work on the problem from a different angle," Freesia McKee, a volunteer, told journalists.

After the rally Stephen Bradberry told the church group volunteers about the struggle faced by residents who have returned to the city and the hurdles placed by various levels of government.

"The people of New Orleans need you to go home and tell your friends, tell you federal representatives about what you’ve seen and heard," said Bradberry. "Our federal government needs to undergo a fundamental shift towards helping all its displaced citizens to realize their rights to return and rebuild their lives and communities."

While many of New Orleans’ displaced residents want to return, they fear the risks of inadequate flood protection in Carrollton-Hollygrove and other areas across the city. Kennedy note that continued government inaction to provide equitable flood protection violates international human rights laws on internal displacement.

During the rally, residents demanded a temporary floodwall be built immediately. New Orleans City councilwoman Shelley Midura, who represents the neighborhood, promised residents that a study to determine the cause of the flooding would begin soon and lead to action by the Sewerage and Water Board to build a flood wall. She remained hopeful that the Army Corps of Engineers could eventually be convinced to build a more permanent flood protection, she said.

About Jeffrey Buchanan

Jeffrey Buchanan is a freelance writer and human rights advocate.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)