Throughout most of my adult life, I have been a student and teacher of history. I have studied and taught the history of Africa and the Middle East, and American history, including the history of immigration to the United States.

During those decades, I considered history a hobby that I somehow turned into a career – something so distant from my personal life. It wasn’t until recently that I began to see the history of U.S. immigration as something that defines the very existence and citizenship of my family in this country.

The realization came last summer, when I followed the footsteps of my paternal grandfather and began working in the manufacturing sector. It was the last place I expected to learn about the life my grandfather might have lived as a new immigrant working in the United States.

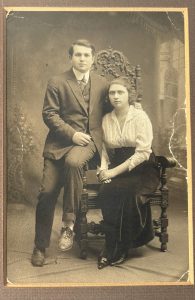

My grandfather arrived from Belarus in 1910. He immediately took a factory job to support his family. He and his siblings shared housing and worked long, grueling hours. Despite the hardships, my grandfather pursued night courses in dentistry at Brooklyn College, N.Y., ultimately earning his degree in 1918. Shortly thereafter, he married my grandmother, whose family hailed from Poland. They had two children, my aunt, Louise, and my father, Max.

Some of my family members never quite assimilated into American culture. My grandmother’s mother, for example, lived in a neighborhood where Russian and Yiddish were the dominant languages. She never became fluent in English. My father, on the other hand, learned very little of either language. His parents were determined that he and Louise should excel in American schools, so they prioritized English fluency.

It is often said that America is a nation of immigrants. Thomas Sowell’s “Ethnic America”, a book published during the Reagan years, chronicles the waves of migration that had shaped this country over the past four centuries. Sowell observed recurring patterns as newcomers moved into established neighborhoods, displacing earlier residents who often relocated to the suburbs. He also noted the groups faced hostilities, which were often compounded by differences in religion, language, and customs. I never met my father’s parents, as they both died in the 1940s, but I remember family members of their generation recounting tales of struggle and perseverance.

The story of migration is not unique to immigrants arriving from abroad. Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns” captures the internal Great Migration of Black Americans fleeing to cities in the northern states to escape the Jim Crow South. Although the north was more welcoming and lacked the overt racism they had fled, they were often subjected to subtler forms of racism and exclusion, such as the redlining laws that denied them access to real estate. Similarly, David Treuer’s “The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee” documents the forced relocations imposed on Native American nations, displacements that began in the 17th century and continued well into the 19th. Even today, leaving what is familiar for a new and often inhospitable setting remains a central theme in the American experience.

I have reflected on these patterns while working in a factory in southeastern Minnesota. The factory floor, where many of my coworkers are first-generation immigrants, has been a surprising classroom. Here, I have learned Somali phrases, improved my Spanish, and developed a taste for tamales and East African sambusas, shared generously during break time. Working side by side with my Muslim colleagues through the entire Ramadan season this year taught me lessons in self-discipline that go well beyond the sacrifices that my Catholic wife makes during Lent.

My colleagues, many who speak English as a second or even third language, have mentored me patiently. Some are much younger than I am, often working their way through college; others have children the same age as mine. During breaks, we swap stories—of children excelling in school, of jobs in the same factory taken up by the next generation. The adage that the first generation does the backbreaking work so the next can thrive feels alive and tangible here.

Not everyone on the factory floor is a recent immigrant. Some of my coworkers trace their roots in the United States back generations, while others are the children or grandchildren of immigrants. The pay and benefits are competitive, and several of my coworkers, having joined right out of high school, have risen through the ranks to hold management positions. The diversity and camaraderie I see every day are a testament to what America has always been: a tapestry of hard work, aspiration, and resilience.

As a former Peace Corps volunteer in Togo, I know what it feels like to be the one person in the room who cannot follow the conversation. My wife, an immigrant herself, worked her way through a GED, community college, and eventually nursing school at the University of Saint Catherine to become a registered nurse. But beyond individual empathy, I have come to see that working together fosters understanding. When you learn someone’s language, hear about their children, and share the rhythms of daily labor, stereotypes fade. Respect takes their place.

My coworkers have taught me that the immigrant experience has always been central to the story of America, with each generation writing a new chapter. Today’s factory floors are no different. The hard work, determination, and sacrifices of immigrant families are a cornerstone of our national narrative, and their contributions—past and present—deserve both recognition and respect. When we listen to the voices of immigrants and those who work alongside them, we hear not just their stories but our own stories. We hear the echoes of America’s enduring promise.

Instead of speaking harshly of immigrants like in the untrue stories that circulated during the last elections about the Haitian workers in Springfield, Ohio, eating pets, we should look at our own history and be grateful that America still attracts immigrants from across the globe.

Could we do a better job of regulating immigration? Of course we could. The elections are over and the need for divisive scapegoating is past. We should approach this as a bipartisan and constructive process that is essential to this nation, because without the diversity of ideas that immigration brings, America would not be the strong country we know today.

About Charlie Cogan

Charles Cogan is a former college administrator and lecturer of history who now works in the manufacturing sector in Minnesota. He has been fascinated by the history of immigration since the early 1980s when he served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Togo. He has previously served on the board of Books for Africa.

(6 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)

(6 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)