During his visit to Ghana, President Barack Obama laid out a U.S. policy that wasn’t any different from that of his predecessors. But because Obama’s father hailed from my home country of Kenya, and because blood – African blood, especially – is thicker than water, Africans exempted their son’s plan for the continent from the tough questions it warranted.

To understand how important blood lines are in Africa, we have to go back to May, when Obama announced his plans to visit Ghana. Euphoria gripped the continent so tightly that instead of talking about what kind of relationship Africa should have with the United States, we went after each other. We wondered why he chose Ghana. Kenyans –- who thought they had an inalienable right to Obama’s first visit as president –- complained that they had been snubbed. Nigeria wondered why Obama didn’t include the African giant in his itinerary. And, if you were Obama, wouldn’t you automatically pick the land that gave the world Nelson Mandela?

In sheer American fashion, Obama explained boldly that he picked Ghana because of the West African nation’s “democratic commitment.”

While Kenyans, Nigerians, South Africans and others were searching their souls, Ghanaians were preparing to do what we Africans do best: dress in colorful attire, sing, dance and chant in praise of presidents.

Although other African countries found their souls very quickly -– “democratic commitment” is such a clear message –- they couldn’t do so in time for Obama to add them to his itinerary. So they joined Ghana and made this “our visit” – a visit to sub-Saharan Africa. After all, isn’t it blood that binds us, and doesn’t an African son belong to the village?

By the time Obama landed in Ghana, we were so unified by this son of Africa that we did not ask him to tell us what the real purpose of his visit to Ghana was, and how his new plan was different from that of his predecessors.

Because Obama is of African blood, no one stood up to tell him that “democratic commitment” is an American buzz phrase we have heard many times, and that, if indeed this was about democracy, Ghana wouldn’t have been the best choice. Doesn’t Ghana have a long history of coups? And didn’t products of those coups rule the country until as recently as 2001?

Couldn’t a better choice have been Tanzania – where three presidents have left office voluntarily, and equal numbers of Muslims, Christians and indigenous believers have learned to coexist peacefully? (According to the CIA World Factbook, Tanzania’s economy grew by 7.1 percent in 2008.) Does the fact that a single party has mostly ruled Tanzania make it less of a democracy?

What about Zambia, where Frederick Chiluba – a former president -– is facing charges for allegedly stealing taxpayers’ money? Yes, President Obama, a court in that supposedly corruption-ridden continent of great suffering has put a former president on trial.

And, by avoiding other African countries, isn’t Obama continuing America’s “old” policies of pitting nations against each other? Isn’t he contradicting the pledge he made on his inauguration day to open dialogue? Even George W. Bush, of “axis of evil” fame, visited five African countries. And, isn’t it stereotypical to slap the “corrupt” label on all African leaders?

“There are wars over land and wars over resources,” Obama said. But his African blood prevented us from asking him whether most of those resources (diamonds) end up in the hands of Africans. What about that other resource that has caused so much havoc in the Niger Delta? Is it because in Nigeria, “the rule of law gives way to the rule of brutality and bribery?” Do the multinationals that give these bribes have any role in this war over resources? And, is there any likelihood that a newfound resource (oil) off Ghana’s coast pushed the country higher on the American chart of “democratic commitment?”

“Africa is not the crude caricature of a continent at war,” Obama said, yet the son of Africa continues to push for the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) –- the same policy of militarization we rejected under Bush. Why did his administration boost funding – from $8.3 million in 2009 to $25.6 million in 2010 – for sale of weapons to some of the same corrupt countries he avoided on his trip? The figure seems meager, but $25.6 million can put at least 25,000 M16 rifles in the hands of some of the corrupt countries. Also, according to Washington, D.C.-based African Security Research Project, the U.S. military is training several African countries including Kenya, Liberia, Rwanda, Uganda, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, under a program called International Military Education and Training (IMET). Obama has also proposed new IMET programs in Somalia, Equatorial Guinea, and Zimbabwe.

Because he has African blood, we were afraid to tell him that it takes more than a couple of brief visits to Africa to understand the continent. We agreed with him that, “Yes, a colonial map that made little sense helped to breed conflict.” But we failed to explain to him that many of the Africans who bring up colonialism do not do so to blame the West. That we have never denied that in Africa corruption exists in endemic proportions; that we mention colonialism for the sake of practicality; that we want the West to understand that a continent brutalized and looted for centuries cannot turn around in 50 years.

We want the United States to look at where it was 50 years after its independence. Were the African slaves free? Could women vote? Had the civil war even happened? Wasn’t corruption rampant in the new, free nation?

But rather than ask this son of Africa to look at history, we let him spit the same Western rhetoric that implies that any African who utters the word “colonialism” wants Africa to wait 200 years for a strong “democratic commitment.” Because Obama is of our blood, we let him continue to push the same flawed, condescending idea that every African is in dire need of water, food and medicine. “And that’s why,” he said, “my administration has committed $63 billion to meet these challenges.”

Or that Africans lack education, when in fact the continent is full of highly educated people capable of solving Africa’s problems. African blood makes us hush instead of telling Obama that what Africans need is an end to the policies that allow multinationals to bribe governments to let them to continue stripping the continent of its wealth.

We cheered when we heard Obama say that America “will put more resources in the hands of those who need it,” even though we know that most of that aid will end up in the hands of our not-so-democratically-committed African-born sons. We applauded when Obama said, “Wealthy nations must open our doors to goods and services from Africa in a meaningful way,” although it’s no secret that even if the entire world opened its market to Africa, most of us would have nothing to sell.

Ironically, Obama’s African blood has made us too blind to see that the heart that pumps it through his veins is American.

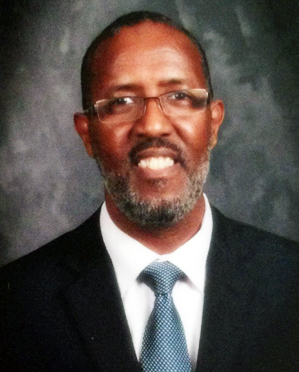

About Edwin Okong'o - Mshale Contributing Editor

Edwin Okong'o is a Mshale Contributing Editor. Formerly he was the newspaper's editor.