Six years ago, a 21-year-old Ethiopian refugee named Oballa Oballa walked into the mayor’s office in Austin, Minn., and asked what he could do for his new community. On Nov. 3, Oballa – who has lived in the United States for only seven years – made history by becoming the first Black person to be elected to the city council of the small city of about 25,000 residents, located 100 miles south of the Twin Cities, near the border with Iowa.

Oballa also became the first person of color and first refugee to be elected to the council in the history of the city, which spans more than 150 years. Since his election, Oballa has been fielding calls from journalists and people wondering how such a young person pulled off such a difficult feat. But to him, it’s not surprising that he ended up in government, he said. His interest in politics and leadership goes back to his early school days.

“All my years as student, I have always wanted to be a leader,” he said during a phone conversation.

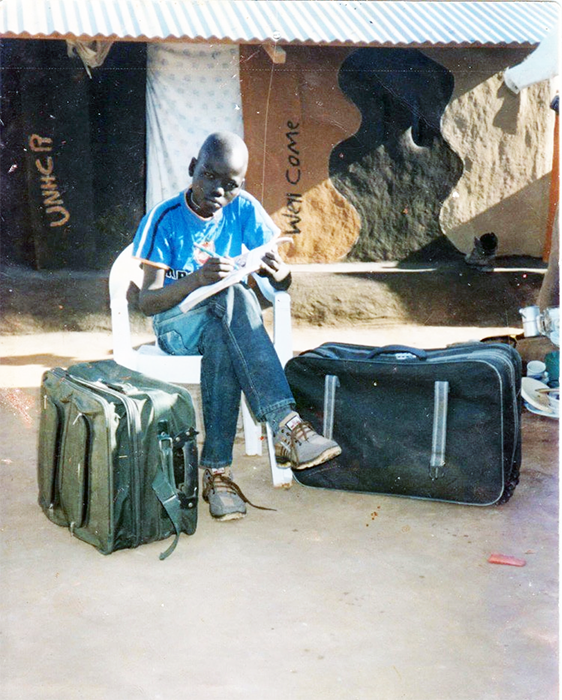

Oballa spent the early part of those school years at Dadaab, a refugee camp in eastern Kenya that is home to more than 200,000 refugees. His family fled there in 2003 from Gambela, Ethiopia, after government forces began massacring his people. Oballa didn’t start formal schooling until he was 11 years old, but once he started, there was no stopping him. During his school years he was a class monitor (president), and a school prefect, the equivalent of a cabinet secretary in student government. He would later rise to become the head boy, a title given to the most senior male student official.

That leadership spirit continued soon after Oballa’s family resettled as refugees in the United States in 2013. He was 20 years old, but still didn’t have a high school diploma. He immediately enrolled at Job Corps in the Twin Cities and “worked so hard” and completed his high school credits in eight months. He soon moved to Austin to begin higher studies at Riverland Community College.

Oballa is one of at least 30 African immigrants and first-generation American citizens of African descent who were candidates in the 2020 U.S. elections. The number may seem insignificant, given that there are more that there are 2.1 million African-born immigrants in the United States, but it is worth noting because Africans haven’t always been active in American politics.

African immigrants have been coming to the United States for at least 60 years. The earliest of them arrived with the sole purpose of getting higher education and going back to take part in building their newly independent countries. They included people like Barack Obama, the man whose eponymous American-born son would become the first black president of the United States. But as governments turned authoritarian, economies stagnated, and wars began to break out in some countries, more Africans began to stay.

By 1970, there were an estimated 80,000 African immigrants living the United States. They made up only 0.8 percent of the total immigrant population, according to a Pew Research Center study that analyzed U.S. Census data. Since then, their population has grown so exponentially that in 2017 it claimed 4.8% of the total foreign-born persons. Most of that growth occurred between 2000 and 2013, when the population of African immigrants increased by a whopping 41 percent.

Still, African immigrants mostly stayed away from active U.S. politics. Even today, there are Africans who have lived in America for decades but who follow the politics of their countries more than they do local affairs in the United States. It is not uncommon to find Africans who travel to the continent to vote and even run for office. But as the increasing number of African immigrants and their descendants in American politics shows, that is changing.

In Colorado’s congressional District 2, Rep. Joe Neguse, whose parents are from Eritrea, easily won re-election for his second term in the U.S. House of Representatives. Also, in Colorado, Naquetta Ricks, who was born in Liberia, was elected to represent District 40 in the state legislature. Another Liberian, Nathan Biah, was elected to represent District 3 in the Rhode Island state legislature. And pharmacist Oye Owolewa became the first Nigerian-American to be elected to represent Washington, D.C. in the U.S. Congress.

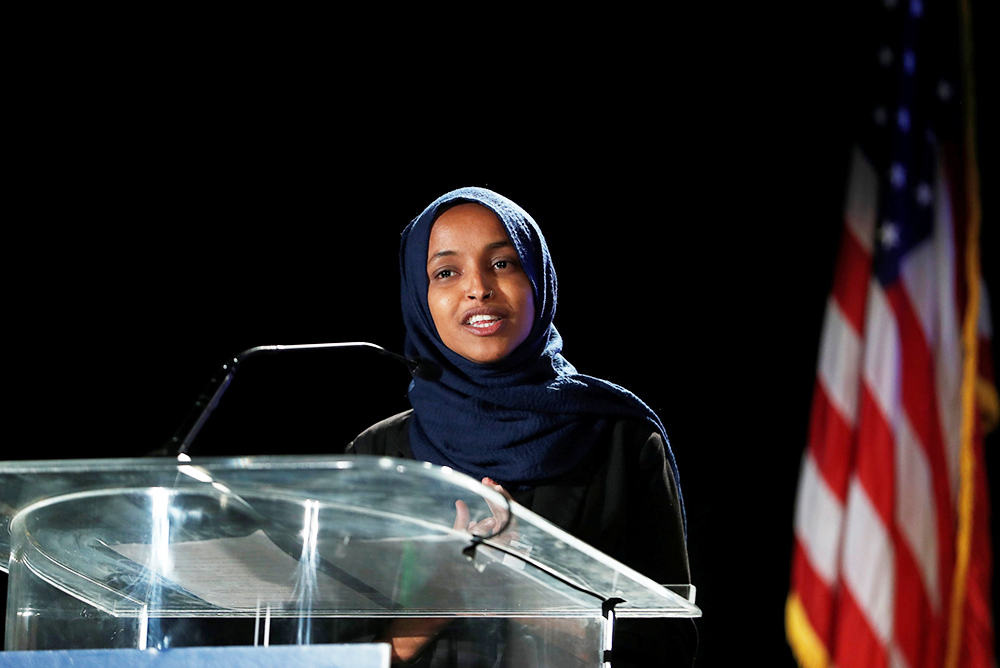

But Minnesota is the epicenter of the recent resurgence of African immigrants in U.S. politics. The most prominent African-born lawmaker is Rep. Ilhan Omar, a refugee from Somalia, who was first elected in 2018 to represent Minnesota’s District 5 in the U.S. Congress. The African immigrant community in Minneapolis was instrumental in her election. But the community’s political achievement in electing Omar has been overshadowed by racist and Islamophobic attacks on her by President Donald Trump, who attempted to make her election a rallying cry in his desperate bid to win Minnesota.

“We’re going to win the state of Minnesota because of her,” Trump said in September. “She’s telling us how to run our country. How did you do where you came from? How is your country doing?”

The president’s strategy, however, backfired by motivating Omar’s constituents to register and vote in large numbers.

‘Africans really stepped up’

“Africans really stepped up,” said Sizi Goyah, a Liberian-born high school mathematics teacher who ran unsuccessfully for a city council seat in the Brooklyn Center suburb of Minneapolis. “Nigerians, Somalis, Liberians, Kenyans, Ethiopians – everyone came together to show that Africans are here and they are not going to be intimidated.”

In the end, Omar got the last laugh by getting re-elected with 64 percent, more than twice the votes of her Republican opponent. Trump, on the other hand, lost Minnesota.

“The irony of Trump saying he would win Minnesota because of [Omar] is that her race once again shattered turnout records,” Jeremy Slevin, Omar’s spokesman, tweeted after the elections. “If anything, he lost Minnesota because of Ilhan’s district.”

Trump’s Democratic Party opponent, Joe Biden, received 80 percent of vote in Omar’s district, by far the most of any of Minnesota’s eight congressional districts.

This year, Africans in Minnesota didn’t just come to vote. They also ran for office in record numbers, and a handful of them were elected. Esther Agbaje, a 34-year old Nigerian-American lawyer, was elected to represent District 59B in the state legislature. Omar Fateh, a Somali-American, won a seat in the state senate. Fateh and Agbaje will join Mohamud Noor, and Hodan Hassan, both of whom are of Somali origin and were re-elected.

What makes Minnesota stand out is the large concentration of African immigrants in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. The state has the fastest growing black population in the United States. The Migration Policy Institute estimates there are over 130,000 African immigrants in the state. Most of them are refugees from Somalia and Liberia. There are also significant numbers of Nigerians, Kenyans and Ethiopians. But Goyah thinks there is another reason why Africans in Minnesota have been so successful in creating a political force.

“People ask why we live and thrive in this cold place, but the hearts of the people of this state are so warm,” Goyah said.

He explained that although systemic racism still exists as evidenced by the killing of George Floyd in June by a Minneapolis police officer, the people of Minnesota are always willing to listen and learn from their mistakes. That mentality is why white Minnesotans are willing to take in refugees and mentor those among them who have political ambitions, he said. It’s that welcoming nature of Minnesotans that helped Oballa make history.

Because Oballa lives in a predominantly white city and too far to benefit from the votes of the large African community in the Twin Cities, he decided to earn the trust of the people of Austin. He began by visiting the mayor’s office soon after he arrived six years ago.

“He came in and said, ‘I am here,’” said Tom Stiehm, the mayor, “and I said ‘So what?’”

Stiehm didn’t ask that to be rude. He just didn’t know how to respond. He couldn’t remember any of the city’s residents ever walking into his office so confidently and declaring that he wanted to help. Certainly, none of the city’s immigrants, who make up 23 percent of its population, had ever done what Oballa did.

Oballa remembers vividly the incident that sent him to the mayor’s office. Soon after moving to Austin, he asked his African immigrant friends – many of whom had lived in Austin for as long as 10 years – if they knew the name of their mayor. They didn’t. He asked if they knew who their councilmember was. They didn’t know that either.

‘How could you live in a city and not know who the people making decisions for you are?’

“I was so shocked,” Oballa remembered. “How could you live in a city and not know who the people making decisions for you are?”

Oballa, who didn’t own a car at that time, walked to City Hall and asked to see the mayor. An assistant asked him if he had an appointment.

“I didn’t know I needed an appointment to see the mayor,” he said, laughing, “because in Africa when you want to see your representative, you just show up and if you have to wait all day to see the official, you wait”

He made an appointment.

“After talking to him for a while, I realized that this is the kind of person we’ve been looking for,” Stiehm said.

The city government had always been looking for ways to engage immigrant communities beyond just providing them with essential services, said Stiehm. But they hadn’t made much progress because most immigrants weren’t usually involved in matters of government.

“I am not an immigrant so it’s difficult for me to know what their specific needs are,” Stiehm said. “Oballa came in at just the right time.”

Oballa made it a habit to volunteer at City Hall. He became an unofficial liaison to the African immigrant community. Stiehm got so impressed that in 2017 he appointed Oballa to the city’s Human Rights Commission (HRC), a nine-member body set up to “eliminate unfair discriminatory practices that are contrary to the public policies of the State of Minnesota.”

“The secret to Oballa’s success is that he works so incredibly hard,” said Jason Baskin, a city council member who served with him on the HRC. “He gets more done in one day than most people do in a month.”

Baskin remembers how important Oballa’s hard work was when Baskin ran for office in two years ago. One day Oballa overheard him wondering how he was going to distribute lawn signs to voters. Oballa volunteered to help.

“I’m thinking, ‘He’s going to take a handful of signs,’” Baskin said, “but by the end of the day 90 percent of them were up because he rallied his college friends to help.”

When Baskin got elected, he and Oballa became even closer. He and the mayor began to encourage Oballa to run for office. But there was one hurdle: Oballa was not a U.S. citizen. He continued to be active as a volunteer at City Hall. When his citizenship application was approved in 2019, he declared his intention to run for the city council.

“Once I got my citizenship, I had no excuse,” Oballa said. “Austin had given me so much. I wanted to give back.”

Baskin describes Oballa as a selfless person, who didn’t run to amass “a bunch of power,” but because he genuinely cares about people. He said Oballa is going to be a role model, not just for people of color, but all Americans.

‘Sometime a lot of us who were born here take for granted the magic of America’

“Sometime a lot of us who were born here take for granted the magic of America,” Baskin said. “When Oballa talks about what’s possible in America, he reminds us that this is a country where living the dream is still possible. When you go around town and hear old white ladies talking about how good he is, it’s just so powerful.”

Oballa said he wanted to take advantage of every opportunity that had been extended to him, so he could be a role model to his child.

“I want my 3-month-old baby to grow up knowing that the dream is still alive, but that you have to get out of your comfort zone and reach out to people of other backgrounds.”

Stiehm, the mayor, thinks Oballa is destined to do more than just inspire his child.

“People who know him know that the city council is only the beginning of this young man’s journey,” Stiehm said. “He’s gonna go far.”

About Edwin Okong'o - Mshale Contributing Editor

Edwin Okong'o is a Mshale Contributing Editor. Formerly he was the newspaper's editor.