East African Traveler

We began the final trek up Mount Kilimanjaro at midnight. Up the last 6000-plus feet to the rooftop of Africa. Up the sheer slope along a zigzagging path of scree and volcanic rock to Uhuru Peak.

“Pole pole,” our guide reminded the four of us as we lugged one foot in front of the other, gasping for breath in the thin mountain air. Pole pole means “slowly slowly” in Swahili, a motto wisely adopted by many climbing teams. Hearing it again boosted our morale, but by that point, slowly was the only way we could take it.

Under a nearly full moon, we faced a dark mass of mountain to which we could see no end. For every three steps in that loose rock, we seemed to slide back one. Fierce wind gusts regularly shook our balance, and temperatures dropped to a deep freeze.

Looking back down at what little progress we had made, we spotted two different clusters of lights: a long train of fellow climbers’ headlamps winding its way up, and, much farther past them, appearing almost as far away as the stars appear above, the lights of downtown Moshi.

But let’s cut to the climax. We all made it. We all stood at Uhuru Peak with freezing toes and faces, some suffering from altitude sickness and exhaustion, others, we would later find out, from pneumonia. We all had our photos taken. We all went down.

I could go on about sunrises over a sea of clouds or gazes into African glaciers. But it has all been written, photographed, and filmed countless times before. Instead, I want to write about what, or rather whom, was missing at the top of our (and every) final ascent.

Our team consisted of two Tanzanian mountaineers, four American travelers, and eight Tanzanian porters. The porters, who stay back at camp during that last climb, inspired awe and reflection in all of us. It’s one thing to see a young man bearing 45 pounds, much of it on his head, for six days up and down a rugged mountain trail. It’s a whole other 19,341-foot-like perspective once you know he is carrying your own bag, with all your gadgets and gear, extra clothing, sleeping bags and air mattresses, or your tents, water, camping equipment, and food for a week. And you only have a daypack with your camera and trail mix.

By the first day when we were still in the forested foothills, all of us realized how helpless we would be without each other and the Tanzanians beside us. A regular Westerner climber taking on Kilimanjaro without porters and guides is like Lance Armstrong winning the Tour de France without a bike.

It’s difficult not to ponder post-colonial legacies in seeing their underpaid day-in-day-out struggle often for the sake of Western tourists’ false sense of accomplishment.

After all, the German explorer, Hans Meyer, has long been credited as the first person to reach Africa’s highest point in 1889, later having both a peak and cave named after him. Few the guidebooks to this day mention Johannes Kinyala Lauwo, a teenage African army scout who happened to climb to the top of Kilimanjaro before Meyer and who even helped Meyer and company up their first trek in which many porters perished.

The guide for our climb, Joseph, came from the same village as Lauwo and has himself made more than sixty climbs. I made him a promise on the way down the mountain that he and his crew would see their names in newspaper print for a change. It’s a pebble-sized token, but the boys will get a kick out of it. Here they are: Joseph, Asantiel, Gaspa, “Little” Joseph, Kornel, Richard, Gaudence, Ndugu, Living, and Deo. Asante marafiki. Thank you, friends. The view was nice, the journey divine.

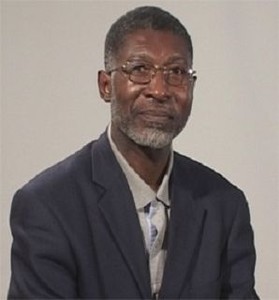

About Jeremy O'Kasick