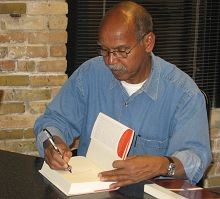

“Literature opens our eyes to the uplifting of human dignity,” were Nuruddin Farah’s opening remarks, as he prepared to read a passage from his latest novel, Knots, to a full house at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis.

Nuruddin Farah, a Somali-born and internationally acclaimed novelist, began his literary career with his first book, From a Crooked Rib in 1970. He has written on various issues including a trilogy on the “Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship” (where he discusses the stripping of Africa by European colonialists and Africa’s current breed of political leaders). Knots is his ninth novel.

Mr. Farah read a passage, from his latest book Knots, where he vividly describes the protagonist, a Somali woman-Cambara, in a physical fight with her husband. She takes out her anger on him, a result of pent-up frustration, after she tastes blood on her lips when he strikes her. The story is a vivid narration of Cambara’s life when she returns, from Canada to Mogadishu in Somalia, to mourn the death of her son. n her war-ravaged homeland she finds succor among women peace activists, who, paradoxically, help her enlist mercenaries to reclaim her family home from a vicious warlord.

Like with most book readings, the audience was excited at the chance to ask Mr. Farah questions. However, what was meant to be a literary discussion on his work inevitably concentrated on the war in Somalia and the role of the Somalia Diaspora in ensuring peace is achieved.

A Somali woman in the audience, in praise of Mr. Farah’s work was impressed that his books advocated for the rights of women. She wondered if Mr. Farah was disappointed in Somali men.

“I am highly disappointed with Somali men, especially those in the Diaspora, and deeply critical of their role in the continued civil war in Somalia. Many Somalis in the Diaspora have worked hard as immigrants to establish themselves overcoming severe hardships and acquiring economic success. However, their interest in Somalia is limited to funding the war instead of working on ways to stop it. The Diaspora achieves political and social freedoms in their newfound homes, however, their fellow men, and their families, in Somalia, are constantly at war.”

Mr. Farah was also critical of what he called the Islamization of Somalia where women are oppressed not only in their role as citizens of Somalia, but also in their dressing. He claimed that it is not in the Somali tradition for women to dress in the burqa (A loose, usually black or light blue robe that is worn by Muslim women, especially in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, and that covers the body from head to toe). A Somali woman urged Mr. Farah to refrain from condemning Islamic women who covered themselves, since for Somali women who have endured a lot during the war; the veil serves as a protection and preservative of self.

Mr. Farah, who seems to have an equal number of critics, as well as fans, within the Somali community, continued to strike a raw nerve with his audience when he urged Somali men to get up from their sit-ins at coffee shops, where they discussed useless politics, and to move back to Somalia. A member of the audience said that perhaps the onus was with the young generation, since the older generation was still tied down to what little memory of the good Somalia that they had.

A young lady in the audience was overwhelmed by meeting Mr. Farah who she considered a true leader of the Somali community, an honor which he politely declined. Neema, a seventeen year old Somali girl protested that she had never known a real home and was in constant strife to find an identity.

Rashid Ali, a college freshman at Minneapolis Community College, wanted to know what Mr. Farah’s most rewarding moment about being an author was, and whence he found his aspiration. Mr. Farah is a professional writer, working from 9 to 5, so according to him he does seek inspiration to write. He has to work at it. His biggest accomplishment is the completion of a book.

While the discussion on Somali politics was passionate and heated, filling the room with tension, a lot of Mr. Farah’s fans left the room disappointed as they had a lot to discuss with the author on his literary work.

One Somali man who wishes to remain anonymous had this to say about the book reading, “Mr. Farah came across as arrogant. He is disconnected from the Somali community. It was a very disappointing and awful event.”

Another one had this to say, “It is sad to see so many critics of Farah that is the saddest thing about Somalis, they never see the beauty about anything. I am an avid reader of Farah’s books. Other great African writers, such as Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka also admire Farah’s writing.”

Mr. Farah also read from Sardines, a passage on the relationship between a mother and her child, reminding the young generation that one must never forget the hand that fed them. Sardines,one of his books that earned him the reputation of being a male-feminist, is a social commentary on life under a dictatorship with a compassionate exploration of African feminist issues.

Mr. Farah was in Minnesota as a resident at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University where he worked with the English, political science, history and peace studies classes at both universities.

About Julia N. Opoti

A former Mshale editor, Julia Nekessa Opoti is now the producer and host of the radio show: Reflections of New Minnesotans on AM950 . She also edits/publishes Kenya Imagine.