When Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi announced in November that Kenyan citizens abroad were on course to set a record in the amount of money they sent home in 2025, many saw it as a cause for celebration.

“This figure has actually hit a trillion [shillings],” he announced jubilantly.

That is approximately $7.7 billion, a tremendous increase from the $5.04 billion sent in 2024. The figure is even more impressive when considering Kenya’s nominal GDP in 2025 is estimated at $136 billion. Although this is often great news for the government, Kenyans abroad usually receive the news with mixed reactions.

Ken Lemaiyan, one of the founders of Kenyans Changing Kenya, a California-based civic organization, said the money he and most of his compatriots sent home was for sustaining families, and for small-scale projects like building residential homes.

“It’s spending, not investing,” Lemayian said. “It’s a lifeline for families – school fees, medicines – but is it building Kenya’s economy?”

Lemaiyan said Kenya needed systems to turn diaspora cash into sustainable projects that can create employment and trigger national growth.

“Otherwise, we’re just surviving, not thriving,” he said.

North America accounts for the largest portion of diaspora remittances to Kenya, according to the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). For example, almost 60% of the $438 million sent home in October came from North America, especially the United States where close to 165,000 Kenyans live, according to the 2024 U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS).

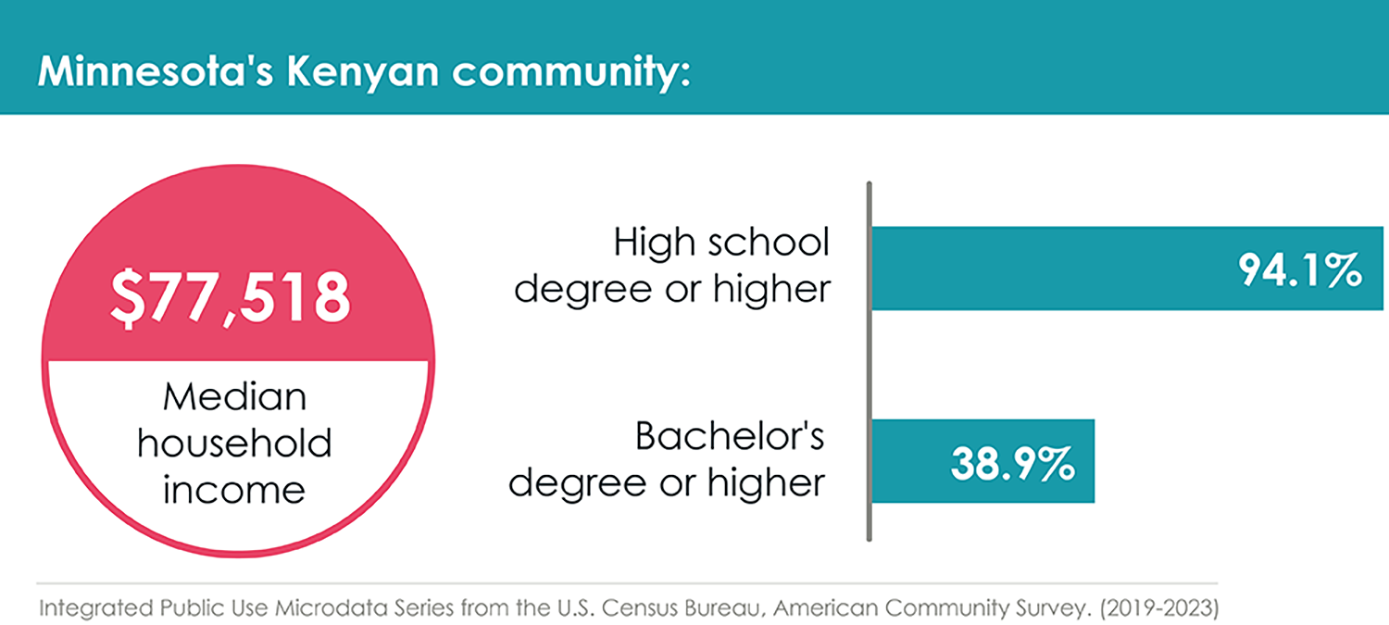

Kenyans in the United States tend to be highly educated. A Minnesota Compass analysis of Integrated Public Use Microdata Series ACS data (2019-2023), for example, found that 94.1% of the Kenyan community in Minnesota, approximately 20,000 people, had a high school diploma or higher, and 38.9% had at least an undergraduate degree.

Numerous studies have shown that that communities with high rates of education have lower unemployment rates and higher earnings, compared to those that don’t. In 2022, for example, a National Center for Education Statistics survey of people aged 25-34 found that median earnings of those with bachelor’s degrees were 59% higher than of those whose highest level of education was high school. The high education attainment is evident in Minnesota’s Kenyan community, with a median household income of $77,518, according to the Minnesota Compass report. That figure is statistically tied with the national median household income of $77,719. This is an indication that the Kenyan community is doing relatively well and could explain the upward trend in remittances.

Samuel Ireri, the group head of international banking and payments at Equity Group, agreed that Kenyan citizens abroad could be much better financially if more of the money they sent home went into stable investments. For more than 23 years he lived in the United States and worked for several banks in the Minneapolis area, including Wells Fargo, and JP Morgan Chase. But he left because he strongly believed he could use what he had learned from the prestigious American banks to bridge the gap in diaspora investments.

“[I was] trying to find a purpose in life,” he said. “How do I serve my country? How can I fill in the gaps with the knowledge, the experience that I had in banking, and in financial services?”

So, when in January an opportunity to join one of the largest private banking and finance companies in Kenya, Ireri didn’t think twice. One of his priorities at Equity was to simplify the process of opening and maintaining accounts online to give Kenyans abroad confidence in the country’s financial system. He took steps to remove obstacles he had encountered as a customer living abroad.

“The load of paperwork,” Ireri said, “the bureaucracy of getting your account up and running, and trying to follow up when there’s an issue, and people not getting back to you.”

Ireri said Equity reduced the paperwork and focused on improving its app so customers could access their accounts remotely. Equity was also working with the CBK to see how it could digitize the process.

Dr. Wilson Endege is the CEO and director of Daktari Biotechnology Ltd (DKTB), an ambitious venture that has been rallying Kenyans abroad to do more than just sending money to relatives. When he graduated from the Free University of Brussels in 1992, he was only the third person from Kenya to earn a doctorate in molecular biology. When he couldn’t find work in Kenya, he left for the United States, where he worked as a scientist at Harvard Medical School, and numerous pharmaceutical companies before leaving to found DKTB. He said for Kenyans and Africans abroad needed to rely less on governments and more on their own ingenuity.

“I’m not saying that the government is not relevant,” Endege said. “I just don’t think they engage [with the diaspora] correctly.”

Endege said African governments had failed to build adequate infrastructure to incentivize their citizens abroad to make sustainable investments that create jobs. He said Africans should emulate Asian countries, which became economic powerhouses because they harnessed the knowledge and power of their diasporas.

“They created opportunities and invited people to bring back technology so that they could start producing some of these products in their own countries,” Endege said. “As a result, some of the big tech companies you see today have come out of those countries.”

To the contrary, he said, African leaders were often skeptical or outright dismissive when their citizens abroad come home with new ideas. Ten years ago, when he founded DKTB, he wanted to develop Diaspora University Town, a city centered around a state-of-the-art research university and a hub for creation of medicines and vaccines for Africa. Endege said DKTB wrote to nearly a dozen county governments seeking partners and land for the project.

“We wanted to direct some of the diaspora resources into a project that would have impact and create opportunities,” Endege said.

When none of them showed interest, DKTB decided to go without the government. They managed to acquire 1,500 acres from a community in Taita-Taveta, a county in southern coastal region. He assembled a team and began pitching the investment idea to the diaspora and is now hoping Kenyan investors will jump on the opportunity.

“Someone has to do it,” he said when asked why, at nearly 70 years old, he should bother. “I think more about the opportunity that has been lost for people, for the country, and someone has to come back and tell them that we need to do this a little bit differently.”

About Edwin Okong'o - Mshale Contributing Editor

Edwin Okong'o is a Mshale Contributing Editor. Formerly he was the newspaper's editor.