The Democratic Republic of Congo is being ravaged by a violence the rest of the world should not ignore. Yet, Western governments continue to send arms deliveries to rebel movements and oppressive governments. Muadi Mukenge, a Congolese women’s rights activist, questions the international community’s willingness to prevent another catastrophe in her country of origin.

As I watched President-elect Barack Obama deliver his acceptance speech and lay out his philosophy of leadership last month, I thought about what it meant to others around the world. I wondered whether the “Yes We Can” message that inspired millions of Americans would spread throughout the African continent and replace the atrocities fueled by poor governance with people-centered initiatives that inspire hope and enable development, equality and justice.

Hope and justice are long overdue in Africa, including in my home country, the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a fresh armed conflict threatens to destabilize a peace process that took many years to achieve. The war between 1998 and 2003 already took 5 million lives. Now a few selfish people are attempting to take the Congo back in time, instead of respecting the efforts at national reconstruction and healing.

There is deep despair, especially among women and girls, who already suffered unspeakable sexual violence during the war and its aftermath. There is also outrage, from not only the Congolese who have suffered directly over the past decade, but from those of us in the diaspora and friends of the Congo, who have contributed energies to rebuild the country since the 2003 peace accord.

Although I have lived in the United States for most of my life, I’m very involved in matters of the African continent. As the head of the Africa program at the Global Fund for Women, I help support women’s groups in sub-Saharan Africa to implement projects that improve the status of women and raise awareness about human rights abuses.

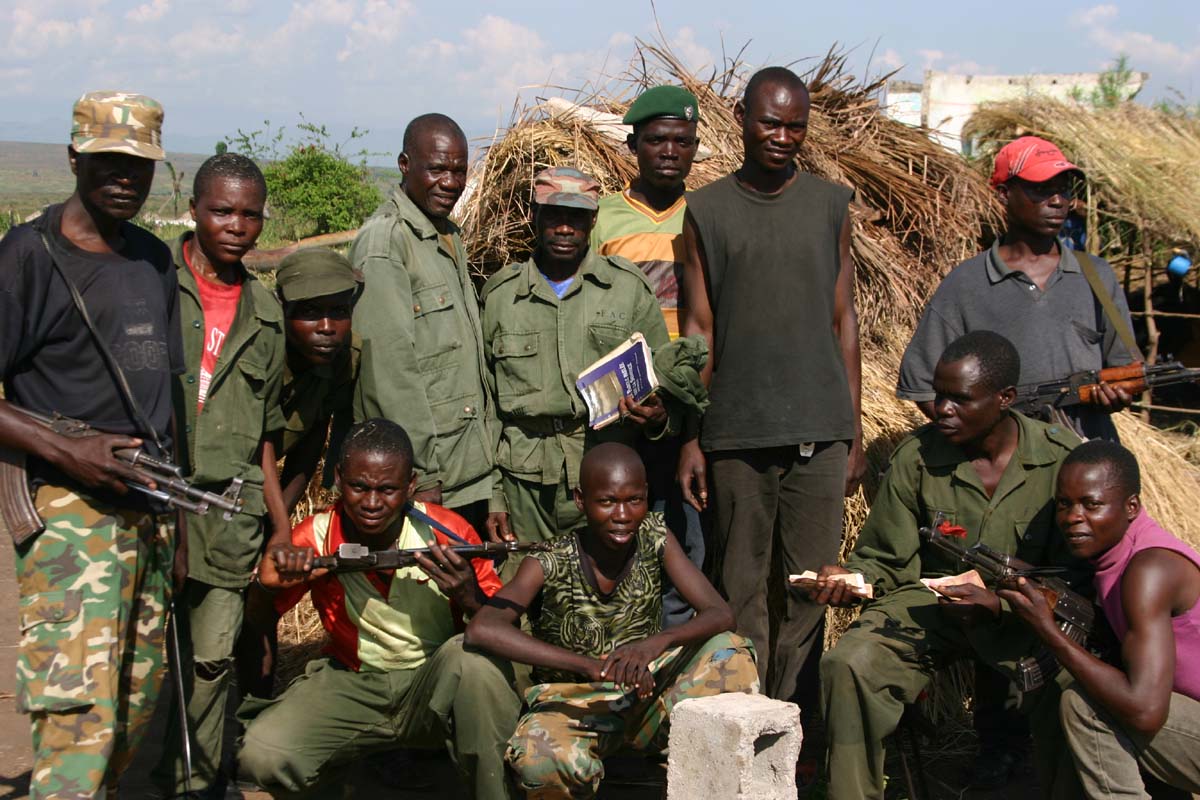

From all indications, it seems that the lives of the Congolese are dispensable. We are dispensable because the hands that send weapons to rebel movements in the Congo are the same ones to rush to send humanitarian aid to fix the damage wreaked by their arms trade. We are dispensable because African leaders – elected or imposed – choose to use these weapons on innocent civilians. We are dispensable because, despite millions of deaths since war broke out in the Congo in 1998, the world still rolls out the red carpet for the National Congress for People’s Defense (CNDP), a rebel army that claims to protect a Tutsi minority in Congo.

Rather than engage directly with the Interhamwe, the Hutu militants who escaped into Congo after committing the genocide in Rwanda, CNDP has taken the easier route of terrorizing Congolese civilians who have nothing to do with persecuting Tutsis. The international community – which is guilty of standing by during the 1994 genocide that took the lives of more than 800,000 people – continues to be hoodwinked by Rwanda, as that country’s government arms a rebel movement likely to fuel another genocide in neighboring Congo.

Congo has over 250 ethnic groups. We are all marginalized, and the millions who have died in Congo’s wars come from all ethnic groups. Yet, we have not taken up guns in the quest for inclusion and resources. The rhetoric from the CNDP is just that – rhetoric. Sadly, profits from armed conflicts and lucrative resources in the Congo are more alluring than any agenda to stop violation of human rights.

Since the recent resumption of the armed conflict in Congo and the displacement of more people, human rights activists have signaled an alarm that those who seek to return to war must be stopped. In mid November, hundreds of women in Goma, Congo, defied the sound of gunfire just outside the city limits and marched to protest the war. Human rights networks in Congo and throughout the world have launched petitions and declarations to condemn the violence and the actions of CNDP. Congolese activists convening at the largest global meeting on women rights hosted by the Association of Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) in Cape Town, read a declaration during the plenary on Nov. 16. Their message is clear: “Enough is enough!”

In September, I visited Congo as part of a solidarity mission headed by the Open Society Institute for Southern Africa (OSISA). Global Fund for Women was invited along with other donors and women’s rights networks from several African countries to learn about challenges facing the women’s rights movement in Congo, as well as key efforts that have been put in place to improve the status of women and girls. But in order for development and human rights to flourish, there must be peace in Congo.

Women members of Parliament shared their priorities with us. They include a work-plan that prioritizes HIV prevention, sexual violence and gender parity; increasing awareness among women elected officials of the national budget process and legislative procedures; passing legislation on the rights of persons living with AIDS; and promoting women’s participation in local elections, especially by expanding their literacy. A key challenge to the Ministry of Gender is the lack of a budget to implement the National Gender Policy.

We visited l’Hopital Muya, a state-run facility that has specialized services for victims of sexual violence. With a grant from the United Nations Population Fund, it’s able to provide comprehensive services, including exams, antibiotics, emergency contraception, post-exposure prophylaxis, counseling, fistula surgery — and all for free. Its services are lifesaving, but they are like a band-aid approach, given that impunity for rape is the norm throughout Congo. Ten percent of the hospital’s patients are under 10 years old. The older clients forego legal support after medical care, afraid to challenge their perpetrators and lacking support from their families, as well as the monetary means to pay legal fees.

We visited mines to witness the working conditions as well as the context under which sexual abuse takes place. As we drove, we passed lines of people making the long trek to dig for diamonds by hand. We passed rows of dilapidated, densely packed wooden structures that double as diamond selling counters, homes and fast-food eateries. We finally arrived at deep excavations with water at the bottom. People dig by hand through the silt water, looking to find a speckle of hope. Women do most of the digging, then leave the sifting to the men to find the nuggets to sell. The girls selling food there make about 20 cents a day. Sexual exploitation and trafficking of minors is rampant. There are terms to refer to girls aged 6 to 8, or 9 to 15. You can make an order just as easily as you can at McDonald’s.

When I think of the women and girls who told us their horrifying experiences of sexual torture, I keep thinking of the modern weapons that make this torture possible, and the origins of these weapons. Certainly, they are not made in Congo.

It is not coincidental that rebel forces armed with sophisticated weapons are in regions where minerals are most abundant. The Congo has been plundered for more than 100 years by explorers, colonial governments, multinational corporations, African opportunists, and a small circle of Congolese leaders. Meanwhile, the majority of the 66 million people in the country don’t have access to food, sanitation, education, transportation, healthcare or justice.

Another major problem the people of Congo face is the United Nation’s slowness to protect them from violence. Many demonstrations have taken place throughout the Congo against the U.N. Mission for its apparent inaction. When will we see bold action to protect Congolese people, especially women?

I am often asked what can be done to help the Congo. There are many efforts undertaken by Congolese women’s rights NGOs to rebuild their country and restore dignity. But these efforts will remain an uphill task as long as Western governments continue to send arms deliveries to rebel movements and oppressive governments.

These efforts will also be in vain as long as the media place the spotlight on the leaders of armed movements that terrorize innocent people. No change will be made when there is no political will to respect past peace talks and accords. The Congolese people are waiting for a time when we will see action, instead of empty proclamations. We are waiting for justice that is long overdue. We know that 5 million deaths constitute genocide. We are waiting for the rest of the world to agree and act with us.

Muadi Mukenge is the regional director for Sub-Saharan Africa at the Global Fund for Women, the largest public foundation exclusively investing in women’s rights groups globally.

About Muadi Mukenge

Muadi Mukenge is the regional director for Sub-Saharan Africa at the Global Fund for Women, the largest public foundation exclusively investing in women's rights groups globally.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)