Today August 28, 2013 is the 50 anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 “I have a Dear Speech”. Nobody can deny the concrete progress of African Americans and other people of color, but the terrible legacy of over three hundred years of slavery, nearly one hundred years of separate but equal treatment of African Americans, and nearly sixty years of some progress laced with subtle racism and continued inequities regarding education, access to credit, and the criminal justice system epitomizes the remaining work to do in the fulfillment of Dr. King’s 1963 “I have a dream speech.” A huge progress was made in so many aspects of American life, but the dream will remain unfilled as long as African American Americans and other people of color do not enjoy equal access to funds, bank loans, credit, home ownership, educations, and equal justice.

Today August 28, 2013 is the 50 anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 “I have a Dear Speech”. Nobody can deny the concrete progress of African Americans and other people of color, but the terrible legacy of over three hundred years of slavery, nearly one hundred years of separate but equal treatment of African Americans, and nearly sixty years of some progress laced with subtle racism and continued inequities regarding education, access to credit, and the criminal justice system epitomizes the remaining work to do in the fulfillment of Dr. King’s 1963 “I have a dream speech.” A huge progress was made in so many aspects of American life, but the dream will remain unfilled as long as African American Americans and other people of color do not enjoy equal access to funds, bank loans, credit, home ownership, educations, and equal justice.

The American dream today is not only for African American only; it is for all the people of color and immigrants of all colors, ethnicity, and creed. The dream remains as unfilled as long as black motorists while (Driving While Black) is something in a wide range of jurisdictions throughout the United States. The dream will remain unfilled as long as public the inequities I public education continues.

The dream remains to be unfilled as long as Fane Mae, Freddie Mac, Wells Fargo, First Union, and multiple banks and mortgage companies and corporations keep on discrimination about African American Americans, and either denying them to have access to a respectful and affordable mortgage that commensurate with their income, putting them in a subprime mortgage despite their comparative qualification for a prime mortgage. These unnecessary impediments have caused a home ownership inequity, a disproportionate number of people of color to unfair foreclosures.

As an immigrant person of color Dr. King’s dream was also our dream, and it was the dream of all immigrants. Dr. King’ dream was not exclusive for African Americans, Like Mahatma Gandhi dream; it is a universal phenomenon of human and civil rights. Yesterday, the dream was to desegregate lunch counters, public schools, colleges, universities, equal employment opportunities, restaurants, and other things. Today’s fight for equity needs to focus on equal opportunity for employment, equal access to credit, high education, and equitable and fair criminal justice system. Yesterdays, the vanguards of the status quo were the local Sharif, police, mayor, or the governor of the highly racially segregated states in the old confederacy.

Yesterday, the pioneers of blatant segregation were Governor George Wallace, Strom Thurmond, Bull, Bull Connor, Richard B. Russell, U.S. senator from Georgia, Lester Maddox of Georgia, John H. Overton, U.S. senator from Louisiana, and many others. Today, the new enforcer of subtle racism, segregation and inequities in employment, education, equal access to credit, and equity in home ownership are bank CEOs, the leaders of some mortgage companies, some local governments and college presidents, boards, or admissions leaders. Much progress has indeed been made.

As a participant in the civil rights movement, I’m proud of that progress. But as long as there is necessity for such a legal category as hate crime, the “Dream” remains unfulfilled. As long as DWB (“Driving While Black”) in the presence of police remains a perilous activity for many African Americans throughout our nation, the Dream remains unfulfilled and diluted. As long as unemployment among African Americans keeps repeating the historic ratio of double the rate of unemployment among white people, the Dream remains unfinished and unfulfilled.

As long as polarization of wealth and absence of equal access to economic opportunity continue to escalate and disproportionately affect African Americans, again the Dream remains unfulfilled. These are not anomalies; they are realities in America. As such, the Dream that Martin Luther King Jr. brought to us remains out of reach and in some cases next to impossible.

Those who argue that our election of an African American president proves that racism is a thing of the past are not looking closely at the subtleties of racism. It is absolutely true the election of to become the first black president of the United States Barack Obama is living proof that tremendous progresses has been made, but there is much work to be done. That unfinished work which is yet to be done, needs a lot of hard work, unity, tremendous focus, and well-planning.

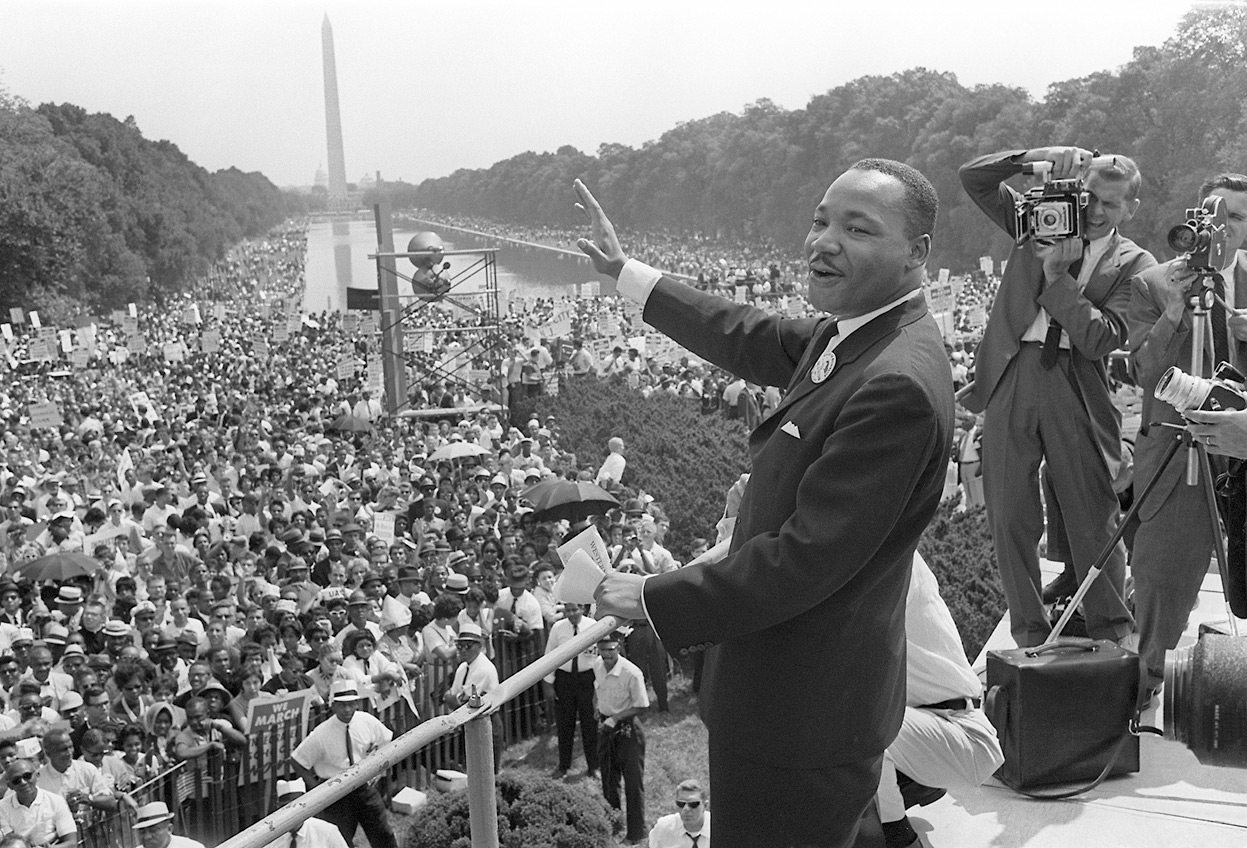

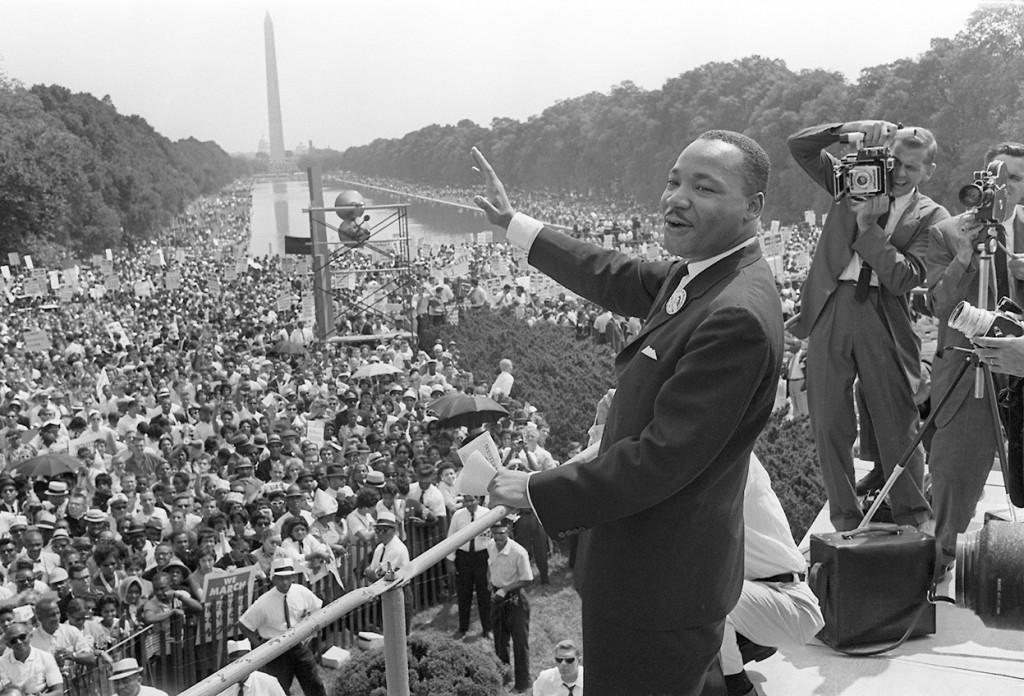

Original March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was one of the largest political rallies for human rights and civil rights in United States history. August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King, Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln, delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech advocating racial harmony during the march. The march was organized by a group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations, under the theme “jobs, and freedom”. Estimates of the number of participants were about quarter of a million. The march was unanimously agreed upon that was instrumental in the passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act 1965.

Although African Americans had been legally freed from slavery, elevated to the status of citizens, and the men given full voting rights at the end of the American Civil War, many continued to face economic and political repression. A system of government sanctioned legal discrimination known as Jim Crow was pervasive in old American South, ensuring that Black Americans remained second-class citizens.

In that backdrop they experienced discrimination from businesses and governments, and in some places were prevented from voting through intimidation, imposition of illegal polls tax and in some cases violence. Twenty-one states prohibited interracial marriage. The momentum for the famous 1963 march on Washington developed over time, and earlier efforts to organize such a demonstration were based on a mass movement of the 1940s. A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, president of the Negro American Labor Council, and vice president of the AFL-CIO was a key instigator in 1941. With Bayard Rustin, Randolph called for 10,000 black workers to march on Washington, in protest of discriminatory hiring by U.S. military contractors and demanding an Executive Order. Faced with a mass march scheduled for July 1, 1941, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on June 25.

The order established the Committee on Fair Employment Practice and banning discriminatory hiring in the defense industry. Randolph called off the March. Randolph and Rustin continued to organize around the idea of a mass march on Washington. They envisioned several large marches during the 1940s, but all were called off. Their Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, held at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, featured by many key leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Roy Wilkins. The 1963 march was an important part of the rapidly growing Civil Rights Movement and struggle, which involved demonstrations and nonviolent direct action across the United States. In 1963 was also marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln. In that back drop violent confrontations have erupted in the South, and especially in Cambridge, Maryland; Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Goldsboro, North Carolina; Somerville, Tennessee; Saint Augustine, Florida; and across Mississippi.

Most of these incidents involved white people retaliating against nonviolent demonstrators Multiple people wanted to march on Washington, but disagreed over how the mechanics of the march. There was widespread criticism that the Kennedy administration had not lived up to its promises in the 1960 election; King described Kennedy’s race policy as “cosmetic.” The public failure of the Baldwin–Kennedy meeting on May 24, 1963, underscored the divide between the needs of Black America and the understanding of Washington politicians. But it also provoked the Kennedys to action on the civil rights issue. On June 11, President Kennedy gave his famous civil rights address on national television and radio, announcing that he would begin to push for civil rights legislation, a law which eventually became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That night, Mississippi activist Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway, further escalating national tension around the issue of racial equality.

Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin began planning the march on Washington in December 1962. They envisioned two days of protest, including sit-ins and lobbying followed by a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. They wanted to focus on joblessness and to call for a public works program that would employ blacks. In early 1963 they called publicly for “a massive March on Washington for jobs. On May 15, 1963, Randolph announced an “October Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs”. He reached out to union leaders, winning the support of the UAW’s Walter Reuther, but not of AFL–CIO president George Meany. Randolph and Rustin intended to focus the March on economic inequality, stating in their original plan that “integration in the fields of education, housing, transportation and public accommodations will be of limited extent and duration so long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persists.” As they negotiated with other leaders, they expanded their stated objectives to “Jobs and Freedom” to acknowledge the agenda of groups that focused more on civil rights.

In June 1963, leaders from several different organizations formed the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, an umbrella group which would coordinate funds and messaging. This coalition of leaders, who became known as the “Big Six”, included: Randolph who was chosen as the titular head of the march, James Farmer (president of the Congress of Racial Equality), Lewis who was the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Martin Luther King, Jr. ,president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference), Roy Wilkins (president of the NAACP), and Whitney Young, the president of the National Urban League. King in particular had become well known for his role in the Birmingham campaign and for his Letter from Birmingham Jail. Wilkins and Young initially objected to Rustin as a leader for the march, because he was a homosexual, a Communist, and a war resistor.[24] They eventually accepted Rustin as deputy organizer, on the condition that Randolph act as lead organizer and manage any political fallout.

On June 22, March organizers, the so-called Big Six met with President Kennedy, who warned against creating “an atmosphere of intimidation” by bringing a large crowd to Washington. The civil rights activists insisted on holding the march. Wilkins pushed for the organizers to rule out civil disobedience described this proposal as the “perfect compromise”. King and Young agreed. Leaders from CORE and SNCC, who wanted to conduct direct actions against the Department of Justice, endorsed the protest before they were informed that civil disobedience would not be allowed. Finalized plans for the March were announced in a press conference on July 2. President Kennedy spoke favorably of the March on July 17, saying that organizers planned a peaceful assembly and had cooperated with the Washington, D.C. police.

March organizers themselves disagreed over the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as epitome of support for a civil rights bill that had been introduced by the Kennedy Administration. Randolph, King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) saw it as a way of raising both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) saw it as a way of challenging and condemning the Kennedy administration’s inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.

Despite their disagreements, the group came together on a set of goals:

• Passage of meaningful civil rights legislation.

• Immediate elimination of school segregation.

• A program of public works, including job training, for the unemployed.

• A Federal law prohibiting discrimination in public or private hiring.

• A $2-an-hour minimum wage nationwide.

• Withholding Federal funds from programs that tolerate discrimination.

• Enforcement of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

• By reducing congressional representation from States that disenfranchise citizens.

• A broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to currently excluded employment areas. Authority for the Attorney General was supposed to institute injunctive suits when constitutional rights are violated. Although in years past Randolph had supported “Negro only” marches, partly to reduce the impression that the civil rights movement was dominated by white communists, organizers in 1963 agreed that whites and blacks marching side by side would create a more powerful image.

The Kennedy administration cooperated with the organizers in planning the March, and one member of the Justice Department was assigned as a full-time liaison. Chicago and New York City as well as some corporations agreed to designate August 28 as “Freedom Day” and give workers the day of. To avoid being perceived as radical, organizers rejected support from Communist groups. However, some politicians claimed that the March was Communist-inspired, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) produced multiple reports suggesting the same. In the days before August 28, the FBI called celebrity backers to inform them of the organizers’ communist connections and advising them to withdraw their support.

When William C. Sullivan produced a lengthy report on August 23 suggesting that Communists had failed to appreciably infiltrate the civil rights movement, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover rejected its contents. Traveling by road, rail, and air, from literally near and far, thousands arrived in Washington D.C. on Wednesday, August 28. Marchers from Boston traveled overnight and arrived in Washington at 7am after an eight-hour trip, but others took much longer bus rides from places like Milwaukee, Little Rock, and St. Louis. Organizers persuaded New York’s MTA to run extra subway trains after midnight on August 28, and the New York City bus terminal was busy throughout the night with peak crowds. A total of 450 buses left New York City from Harlem.

All in all, the original objective of the organizers of the 1963 march was the obtainment for equal employments, voting rights, and social justice. Fifty years after the march, the same issues ranging from discrimination, equal employment opportunities and equal voting rights are still standing.

About Suleiman Egeh

Suleiman Egeh is a science instructor and writer focusing on the Middle East, Horn of Africa and the African Diaspora.