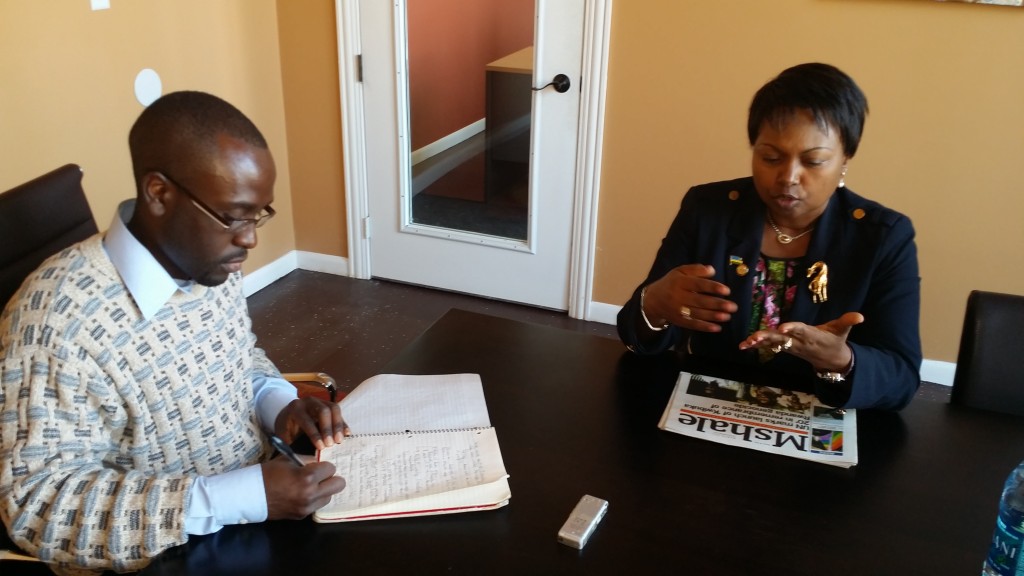

April marked the start of Kwibuka 20 events to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda. The word “kwibuka” means to remember in the Kinyarwanda language. Mathilde Mukantabana, Rwanda’s Ambassador to the United States spoke on the genocide at the University of St. Thomas campus in Minneapolis on Monday. She appeared as a guest of the Minnesota International Center.

“Sometimes we look at Rwanda with genocide, Most of the time we don’t look at the incredible culture, the people,” said Mukantabana. “We are talking about a land smaller than Maryland where a million people died in three months. It is not just the dead but also the people who carry the burden.

Mukantabana also detailed Rwanda’s social and economic progress. Unprecedented investments in universal health care, education and infrastructure have led the nation to relative peace and stability, she said, a far cry from the Rwanda of her youth.

Tensions between the Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups made her into a teenage refugee before her parents became victims of genocide, the ambassador said.

“It shows in my own small, micro level, that genocide was not something spontaneous that came overnight,” she said. “It had been prepared over many years.”

Mukantabana, herself a Tutsi, remembers waking up one and hearing there were no Tutsis in her school, though quotas were already enforced. Some were kicked out. Others died, she said. That kind of cyclical massacre of the Tutsis had started in 1959, after Rwanda gained independence from Belgian colonial rule. According to the CIA world fact book, an estimated 150,000 Tutsis became refugees in the years that followed. Mukantabana also took what she called the road into exile.

“You have those waves of killing that lead eventually to the genocide of 1994,” said Mukantabana. “It had been prepared by years of discrimination, oppression. We moved from the protection of what a citizen can expect from their own state.”

Tutsis who escaped the massacres had to find their own ways in foreign countries, Mukantabana said. She continued her education in Burundi, where she fed a passion for history. She eventually finished high school and her undergraduate degree before she came to the United States. She became a tenured professor in 1994, just before genocide was unleashed.

Mukantabana saw the situation as a reflection of failed institutions, from the state down to the family. It is the state’s responsibility to protect the freedom and human rights of all people within its borders, she said.

“Genocide completely destroys all the social ties. Most people in California where we were also lost loved ones.” Mukantabana said. “People were suffering but nobody was there. We felt a need for people that were trained to deal with that incredible loss.”

To meet that need Mukantabana founded Friends of Rwanda Association, with a three-tiered mission to provide relieve and foster friendship for the mutual survival of her people. She also began to speak against the genocide, which displaced over 4 million people.

In 1999, Rwanda reached a turning point of its own. To take pressure off of the overwhelmed court systems, the government implemented Gacaca, based on a traditional conflict resolution strategy which roughly translates as “judgment on the grass.”

Meanwhile, Mukantabana began to study social work and community organizing for the sake of her people in Rwanda. Social work Social work is an all-encompassing program that deals with trauma and poverty at an individual level but also facilitates communication between human services and institutions, she said. The curriculum she developed as a result was first at taught at Rwanda’s National University in 2000.

A constitutional overhaul in 2003 prioritized gender equity and has helped elevate women to postions of power in public and private institutions. Citizens voted to maintain the percentage of women in parliament at 64 percent since 2013 elections.

Combating the public health crisis that rode on the heels of the genocide, universal health care has doubled life expectancy in Rwanda, according to a report released in the scientific journal Lancet just last year.

“Mother and infant mortality have been reduced, said Mukantabana, which has helped to put Rwanda on track to meet the United Nations Millennium goals.

“Chronic diseases have been managed, especially AIDS, because we have medication, education and many other things that are tied into this,” she said. “In the poorest village, people are being treated. Chronic disease is not so much like a death sentence.”

For the ambassador, the important thing is to provide Rwandans with the freedom from want, fundamental to all other freedoms, she said.

Questions about press freedom linger in the wake of policy which aims to curb the use of mass media to sustain and propagate ethnic hatred. The ambassador said that the recent declarations of press freedom and the sheer number of publications make clear that change is in effect.

“We are looking for an informed population. Right now over 40 percent of our budget is education,” the ambassador said.” We have promoted compulsory education from the primary to the secondary level. At the third level, we are promoting quality education in higher learning.”

But in a country where over half the population is below the age of 20, the horrors of the past are something of a distant memory and the potential failure to learn from history carries risks, said Mukantabana.

This has also fed tensions within the country and throughout the international community, the ambassador said. There are those who believe the narrative of genocide is a tool by which the Kagame administration maintains power and wish to turn this to a political advantage, she said, but this not unprecedented. She used Holocaust deniers as a prime example.

Rwanda has accepted its own liability, in service of nation’s ongoing reconciliation process, the ambassador said, but there are other key players in the genocide that have not yet done so.

“We understood that our genocide would be denied as well. But it is something we have to constantly, constantly fight against,” she said.

In light of her personal losses and the broad scope of her public life, Mukantabana reminded her audience why the lessons history teaches remain unparalleled.

“That’s what Rwanda is trying to do. Not so much to shame anybody, not say, ‘you’ve done that’ but to look at that collectively and say, this is a dark part of our history, Mukantabana said.

“But you can move forward and you can actually find strength by acknowledging even your frailties as human being.”

About Senah Yeboah-Sampong

Senah Yeboah-Sampong is a graduate of Columbia College in Chicago, Illinois with a Bachelors in Journalism, News Writing and Reporting. He covers general assignments for Mshale.