Africa is not a place that usually comes to mind when one thinks of great art festivals. Following independence, African countries mostly focused on the area of academics that had the potential to lead to white-collar jobs. Arts education was almost nonexistent, as art was seen as something to do only after all else had failed. The idea that someone would make a living from selling art was laughable in those days.

But there is evidence that Africa’s attitude towards art is changing. A recent street art festival on the continent attracted an estimated 30,000 attendees. Now in its eighth year, the Chale Wote Street Art Festival is a sensory delight featuring: films, panel discussions, live art performances, visual art, night parties, and traditional processions. This year the festival added extreme sports to its diverse list of events. Each year, Chale Wote transforms Accra’s oldest neighborhood, Jamestown, a major port during the colonial era into one large roaming party, where people go to see as much as to be seen.

According to its founders, Chale Wote’s “vision is to cultivate a wider audience for the arts in West Africa by breaking creative boundaries and using art as a viable form to rejuvenate public spaces.” This year’s theme was “Para-other,” briefly defined in a statement as a, “transatlantic shortwave that transcends language and geography.”

With over 200 artists from various countries exhibiting their work, hundreds of vendors selling everything from kebabs to palm wine to locally designed merchandise and of course, art, there was no shortage of things to see or love about Chale Wote. The festival is also undoubtedly one of Africa’s boldest attempts at creative placemaking.

Creative placemaking is the concept of engaging arts, culture, and creativity to transform neighborhoods. It involves public-private collaborations that use art to revitalize spaces, create economic opportunities and strengthen a sense of community. Creative placemaking has become fully entrenched in the West (including in cities like St. Paul, Minn.) as a means to spur local economies and create a sense of belonging for residents. However, the story in Africa is far different where the arts remain greatly underfunded and where public art is often seen as a nuisance rather than an additive to a functioning society. Yet the massive economic potential creative placemaking has for the African continent cannot be understated as one experiences Chale Wote.

Hakeem Adams, one the festival’s organizers and a 2018 Chale Wote participating artist, estimates that attendance of the festival grew over the last year due to its popularity.

“On Friday night, the High Street in Jamestown, the main artery of the festival, was already shut down by anticipating patrons of the festival, as work for the weekend was being installed,” Adams told me.

Most of Chale Wote’s activities leading up to its main weekend took place outside of Jamestown as artists prepare their art installations to be premiered over the weekend. Come Saturday morning, a large swath of High Street was blocked closed to all vehicular traffic through the weekend. Having visited many of the Jamestown festival sites earlier in the week to familiarize myself with the venue, there was a sense of disbelief when I returned in the high heat of Saturday afternoon.

Above the steady stream of afrobeat music pulsating from speakers were throngs of people where none had been. The small colorful shacks that sat next to High Street when I visited earlier in the week were barely visible through the thick of vendors, curious children running around, and the roving performers in full costumes who stopped crowds so often that I wondered how they made it from one end of the festival street to the other. There was a buoyancy in the air. People danced. Ate. Snapped selfies. Took photos of the art and performers. Everyone was there for the same purpose: to have a good time while consuming art. A sentiment that Adams shared.

“I tell a lot of people that Chale Wote changed my life, and this is even before I exhibited work at the festival,” he said. “Over the past eight years, this event has almost single handedly altered the way in which art of whatever form is seen in Ghana. The impact is immense in shaping young impressionable minds like mine.”

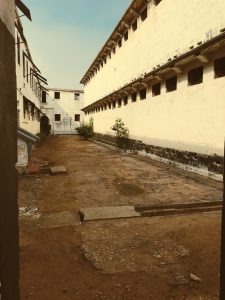

Chale Wote indigenizes creative placemaking by marrying African rituals with modern takes on visual and performance art. And this by far, is what makes it so special. Take for instance multi-disciplinary artist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi’s live performance, “agbaWnu”, held in the courtyard of Fort James. Covered in mud and appearing nude Fiatsi lay seemingly embedded amongst corroded metal spikes while a young girl in tattered clothes sat underneath him playing haunting melodies on a flute. All of this encased in a large metal frame that viewers could walk around. Serving as an eerie reminder of the imprisonment of African bodies performed in a Fort that had served as a prison up until 2008.

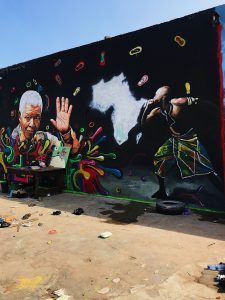

Meanwhile around the corner from Fiatsi’s performance, visual art was exhibited in prison cells with doors flung open. And further back, a traditional healer, dressed in full traditional regalia sat taking clients in one of the Fort’s open corridors. Back on High Street, young boys on bicycles did impressive tricks – spins and flips that seemed to defy gravity – while groups of friends posed for photos in front of graffiti laden walls. This is the juxtaposition of Chale Wote: a constant reminder of the past while reflecting on the present.

To begin to understand the economic impact of the festival, however, one must first understand Jamestown itself, a neighborhood whose past glory is long gone and which has quickly slipped into one of the poorest communities in Accra. So much so that as I marveled to a friend, a local, about the beach access in Jamestown, he quipped, “You know Jamestown is basically Kibera on the ocean, right? It’s a slum.”

“Yes, I know.” I wanted to utter back that I saw how Jamestown mirrored Kenya’s largest slum. But amidst the art and the revelry that fact had been lost.

Jamestown still holds some of Accra’s treasured historical monuments which form the canvasses the artists use each year. From James Fort to Ussher Fort to Otumblohm Square, the shells and hulks of buildings hundreds of years older than the residents of Accra are given new life. And this poor residential fishing community is transformed into one of Africa’s largest art festivals for just one weekend. Many of the food and beverage vendors that line the streets are from Jamestown as are the costumed performers who earn quick money with festival goers eager to take photos with them. Likewise, many participating artists, including the festival organizers, ACCRA [dot] ALT, call Jamestown home.

That for the first time, the Ghana Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture offered financial support to the tune of GHc 300,000 (approx. $63,000) for the festival is proof of the potential and the impact that the festival already has. I asked Fiatsi about his experience as a first-time artist at Chale Wote.

“It was, to me, pilgrimage. Perhaps Mecca where people came to renew their souls, minds and make new covenants to humanity while experiencing all forms of art.”

One can only hope that in many ways Chale Wote will be the next Carnival or Mardi Gras. Each celebrating the unique remembrances of a way of being. This one, paying homage to the many ways of being African.

About Kari Mugo, Mshale Staff Writer

Kari, formerly of Minneapolis is now based in Nairobi. She is a writer, born and raised in Kenya, and a true global citizen. When not writing for Mshale, she is actively pursuing justice and equality for all through her writing and activism.