President Joe Biden’s chief medical adviser on Covid-19, Dr. Anthony Fauci, and Muslim-American doctors asked health care professionals to engage vaccine skeptics in minority communities, and to distinguish them from antivaccine conspiracy theorists.

“You have to respect people’s skepticism and don’t immediately jump on them and criticize them for it,” Fauci said. “Rather than telling them that they have no idea what they are talking about, I think you need to embrace them and engage them.”

Fauci advised medical practitioners to instead put more effort into explaining to skeptics the dominant role science plays in the implementation of public health measures.

“In the history of everything we’ve done in public health, there is no doubt that scientific data leads to the best outcomes,” Fauci said. “We just need to convince people who have skepticism about the scientific method.”

Fauci was speaking Thursday during an online conference held by Illinois-based American Muslim Health Professionals, and moderated by Dr. Hasan Shanawani, the organization’s president.

The speed at which the Covid-19 vaccine was developed – 11 months – has led to millions of people around the world questioning its safety. Previously, the fastest vaccine to go from development to distribution was the one for mumps, which was done in four years in the 1960s. Covid-19 vaccine Skepticism is higher among minority communities, especially African Americans, who in the past have been used by governments as experimental guinea pigs. The most famous was the Tuskegee Study during which researchers injected African-American men who had served in the military with syphilis, under pretense of providing them with free health care. The participants – whose consent was never sought – were left untreated for years.

Another panelist, Dr. Shereef Elnahal, a physician who is the president and CEO of University Hospital in Newark, N.J., said that given that history, it was understandable that people of color would be hesitant to accept the Covid-19 vaccine.

“That skepticism is well rooted in the history of systemic racism, sometimes by the medical establishment itself against the very communities we’re trying to convince right now to take this vaccine,” Elnahal said. “The history of slavery also involved people doing experimental surgeries, gynecological surgeries, on enslaved women.”

Elnahal said because of those past injustices against people of color, today’s medical practitioners must work harder to earn their trust.

“People take that and say, ‘Why should we trust the medical establishment, the government, that has done this to us before?’” Elnahal said. “So, we have to walk through that door of trust, and that takes time.”

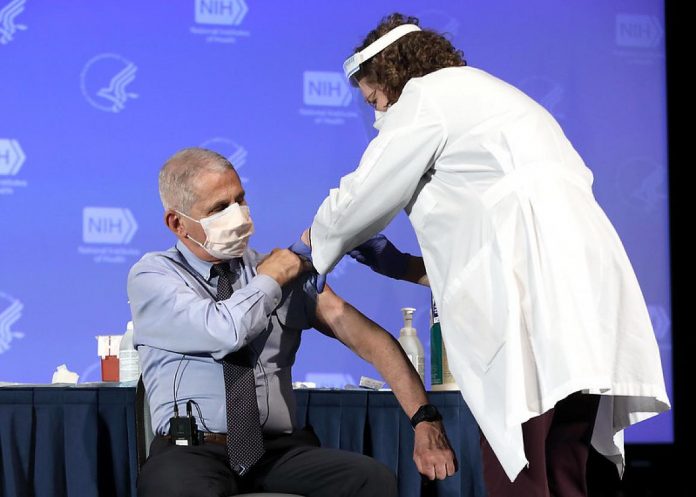

Elnahal said leaders of medical and government institutions could start improving how communities of color perceive them “by earning the badge of trustworthiness” and showing that they are willing to participate in clinical trials and take the vaccine themselves.

“We have to show that we are also willing to sit there and listen, and acknowledge the fact that that skepticism is well rooted and very different from the quote, unquote, anti-vaccinator campaign of misinformation and disinformation,” Elnahal said. “Once you establish that trust, you can start to answer some of the scientific questions.”

Addressing the speed of development question, Fauci explained that scientific advancements that had been taking place at least a decade before January 2020, when scientists began the process of developing a vaccine for the coronavirus, played a significant role in cutting down the time it took.

“It is true that it was extraordinarily fast, relatively speaking, but the point we need to make to people who question that is that this was speed as a result of scientific advances, not as a result of cutting corners, or as the result of being recklessly fast,” Fauci said. “That was not [done] by compromising safety, nor by compromising scientific integrity.”

Dr. Noor Jihan Abdul-Haqq, a pediatrician based in Oklahoma City who is also a member of the National Black Muslim Covid Coalition, said misinformation about the Covid-19 vaccine was also making parents question other vaccines. Many parents had gone to her saying they had heard that children’s vaccines were being injected with the coronavirus, she said. Several had gone as far as refusing to get their children any more immunizations, she said. Abdul-Haqq said that those who had the knowledge should continue to speak out and to engage members of the vulnerable communities they serve in order to counter the spread of misinformation, though she admitted that it was not going to be easy.

“How do I explain the truth in the scientific process to someone who maybe hates science, someone who never took a science class outside of what was recommended in high school?” Abdul-Haqq said. “It’s going to take a lot of time.”

Elnahal said because faith-based organizations like churches and mosques had earned the trust of people through decades of service to the communities, they could help health professionals increase trust of vaccines and public health officials and institutions in general. He said in New Jersey, health care professionals were already working with religious leaders and had had several of them take the Covid-19 vaccine publicly. He said that by one influential Newark pastor alone taking the vaccine, public health officers saw the enrollment of people to be vaccinated go up by 50 percent in the two days that followed.

“We have a lot of work to do in building that trust, but making sure you focus on people who are already trusted as leaders and can be your ambassadors is very important, and I do think the Muslim community is a big part of that,” Elnahal said. “I know that there have been troubling narratives and disinformation circling communities of faith and our faith for quite some time, so we do need Imams side by side with us taking vaccines themselves, hopefully, but very importantly spreading the message to folks who go to their mosques.”

Abdul-Haqq said she deeply relied on her faith to combat misinformation about vaccines, and urged other health care professionals who believe in God to use their faith to challenge myths, especially those rooted in religious beliefs.

“If we truly are believers in God, and we feel that He controls everything, then what makes us believe that He is not the one who assisted mankind to actually produce a vaccine?”

About Edwin Okong'o - Mshale Contributing Editor

Edwin Okong'o is a Mshale Contributing Editor. Formerly he was the newspaper's editor.

Would it help if Muslim politicians would take the vaccine and be videod while being vaccinated?

Comments are closed.