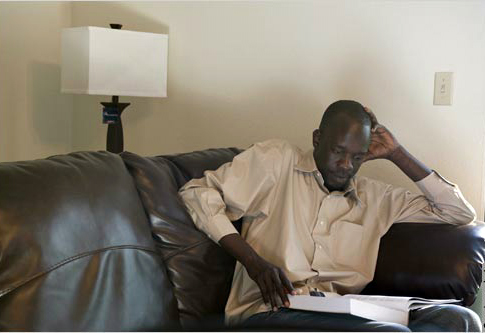

Adier Deng fled his home in southern Sudan at the age of 4 in 1989 during the Second Sudanese Civil War. He was separated from his family, who now live in a refugee camp in Uganda. Deng’s mother died on the way to the camp.

After an arduous journey to Ethiopia and to a refugee camp in Kenya, Deng was resettled in the United States at the age of 15. Now, already having earned a master’s degree in business administration, Deng is in law school and also works as a human rights officer at the Diocese of Kansas City–St. Joseph, helping newly arrived refugees.

Why did you leave your home in southern Sudan?

I left my home in Sudan because of the war that took place since the ‘80s between Northern Sudan and Southern Sudan. I had to escape for safety; we were chased out of our villages when I was 4 years old and had to flee to Ethiopia.

Were you with your family when you left Sudan?

[I was] not [with] my family. My family [was] in the village and I worked in the cattle camp at the time. The cattle camp and the village were attacked separately and we were forced to flee to different directions. My parents [fled] south towards Uganda and I [fled] east [toward] Ethiopia. So I was separated [from] them. I was with my cousin; he was 11 years old at the time.

How long did it take for you and your cousin to get from Sudan to Ethiopia?

It took us about three months to go there because we had to cross a desert and then from there we went to the border, which took us a long time because it was a jungle. It was almost 3,000 miles [4,428 kilometers] to go to Ethiopia so it took us almost three months to go there.

What happened when you got to Ethiopia?

When we got to Ethiopia, we crossed the Gila River, [which] is one of the most dangerous and highly infested rivers in Ethiopia. And I would say maybe in Africa, at large. A lot of our guys lost their lives in the waters, either eaten by crocodiles or drowned. We had to cross that river [to get to] Ethiopia. And then we just had to settle down there and build our own huts by ourselves. At the time, there was no U.N. [United Nations]. There was no one around. We were in the jungle. And we are far away from the cities in Ethiopia — that really [made] it a little difficult for us.

What happened after you were in Ethiopia?

A war broke out in Ethiopia, and then no one wanted us to be there. So we were actually chased back at gunpoint to Sudan and we had to cross the same river again. This time, we were heading to Kenya. This was about 2,000 miles [3,219 kilometers] from where we were at the river. [Going] from Sudan to Ethiopia and then to Kenya took almost a year.

How did you survive?

Basically, it was through my cousin and also the faith that I [had] and the hope. Those were the ones that I was relying on. I was still hoping that things would get better one day; the war is going to be over and I will [be able to] return back to my homeland.

And at the same time, I had to eat what everyone was eating — either being leaves or anything. [I tried not to] think about my parents because the minute [I would] do that, I would lose hope. [I was] just hoping that I will make it. That’s what makes [hope] alive. Just pray — things like that.

What happened when you arrived in Kenya?

We started living in Kenya by the border [with Ethiopia], a place called Lokichoggio. Then we were taken to the northern side of Kenya. There were no buildings. There was no water, just dry land. We [were] now in a place called Kakuma Refugee Camp. [Eventually] the Red Cross and UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund] started to bring in some supplies, books, pencils, some things like that.

What was life like in the refugee camp?

When I arrived in the refugee camp I was turning 5 years old. The life [in the camp] was not good. It was terrible. In the camp, we didn’t have enough [for] basic needs. At the same time, we wanted to go to school. [But] if you don’t have anything to eat, there’s no way that you can go to school. And there was a lot of sickness. Basically, all of the life was not good in the refugee camp, and I was in the camp for nine-and-a-half years.

Where did you want to resettle?

I wanted to go to the U.S. That was the best place possible. I wanted to come to America so that I can go to school and someday contribute to the peace process in Sudan.

What year did you and your cousin leave Kenya for the United States?

It was in November 2000 and I was turning 15.

Who sponsored you?

I was sponsored by Bethany Christian Services in Grand Rapids, Michigan. They located a foster family [for me and] I stayed with them until I turned 18. They were really good. They were like parents.

Describe your arrival in the United States.

It was wintertime and I [hadn’t experienced] winter before. I’m talking about snow. It was real cold. I saw they were holding my name on a small poster board. … I came out and then I saw my name and I came to them. I introduced myself and I was the right person that they were waiting for and they had a big jacket and other clothes to wear. And then I had to put those ones on and we went to the car so we could go home. I was really excited to meet them.

How was it adjusting to life in the United States?

It was really difficult to get adjusted. Basically, the culture is different. [I had] culture shock. I had to get used to American food, to the winters, and going to new schools. When I arrived I could understand English but I [could not] really speak it. So it was a difficult time for me to really put all of this together.

How did you finally start to get more adjusted to your new life?

A: Well, it started with being able to settle down. Just being able to find your niche and what you want to do and getting advice. … There was a Bethany Christian Services program … playing some sports and things like that. [I got] friends. It was a good experience. But at the same time, yeah, you have to have in mind why — the reasons that brought you to America. Those are the reasons that will keep you going.

And what did you want to do?

A: Basically, what I wanted to do was to finish education. That was number one — that was my priority. … [Second], working at an organization that will help, especially the Third World countries that have orphanages or an organization that would take care of that. Or if I don’t find something like that, then I will have to found one by myself.

After so many years of being on the run, how did it feel to finally have a stable home?

It feels good. The security is good over here. At the same time, you still have that feeling that … you want to do something [for] the place that you left. I still feel that I have to work harder. I have to help in some way.

What was high school like?

High school was really good — it was great. I [loved] it.

What were some things that you loved about it?

Having a lot of friends, and, at the same time, the instruction, the teachers, were really, really good. I [loved] playing with kids, going to classes and going out. Life was good. It was really good.

What did you do after high school?

A: After high school, I went to college. I went to Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. I finished my bachelor’s degree in 2007. After that, I studied business at John F. Kennedy University and I finished my MBA in 2008.

What are you doing now?

A: Now, I’m in law school at Concord Law School. And that feels good. Law school is not simple. It is expensive and takes time. But it’s going well so far.

While you are in law school you are also working. Where do you work?

A: I’m working at the Diocese of Kansas City–St. Joseph and I’m human rights officer. I find jobs for refugees. Given the kind of situation [economic recession] that we’re in now, finding a job is a big deal for immigrants. I like what I’m doing. And definitely, it’s the kind of things that I had been through since I came to America. And I have the motivation. I like what I do.

How do you think your background as a refugee has helped you in your job now?

A: It has helped me a lot because, basically, I find myself wearing two lenses. One is being a refugee — I have been in your shoes, I’ve been there. And another thing is being an American. So you have to put these two things together so that you can deliver a good [service]. And at the same time, you have to have some strategic vision to do good things.

[I] know exactly what to do because my mind just flashes back. [For example], if a client called me and said, “Hey, I’m supposed to be going to work today and I don’t have a ride,” my mind would flash back. I was that person not long ago and I know how they feel.

Do you feel at home in the United States?

A: Where you are is basically your home. I feel at home [in the U.S.]. Here, I’m going to school. I have a job and I have my apartment. And I have a lot of networks, a lot of friends. I know the system in the U.S. And I know how to do my things by myself. I got used to the American ways of doing things.

How do you identify yourself?

[Chuckles] I’m still both [Sudanese and American]. Well, I am an American citizen so I am an American. That’s number one. Either domestically or citizenship-wise, I am an American. Number two, I’m still a Sudanese because I am originally from Sudan.

And I still — I’m forming both cultures — American culture and the Sudanese culture as well. That’s a part of the culture that’s not going to go away. So I have these two things still going on, running on. I still speak my language, which is good. And I’m now talking in English, which is really another good thing. So I’m in two worlds. But again, I am in America. It’s good keeping your identity. At the same time, you don’t need to reject a new system that you [are] introduced into.

How did you feel on the day you became a citizen?

I felt really good. I was happy to do it. I had stayed here for a long time and it was time to become a citizen. So [embracing] my new culture and my new country was really good. And I wanted to do that.

How did you achieve so much in such a short time?

I think the thing that you have to remember is make sure you don’t lose your vision. And those were the visions, the objectives that I set aside for myself. It was harder going there. But at the same time, the way that I’ve done it is to make sure you’re studying how to achieve things. You have to plan, then you have to prepare yourself for it and then you have to proceed without being instructed by other actors in the environment or in the community. So those are the ways to approaching it and that’s how I approached them: not [to] lose your vision. And then you have to know how to go about it. A lot of people don’t share those kind of visions or get lost somehow on the way. But again, it’s a personal way of doing things.

About Mshale Staff