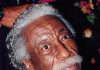

A Liberian diplomat who risked his life to help the United States negotiate the end second civil war in his west African homeland has been honored as one of the “Heroes of U.S. Diplomacy” by the Foreign Service Institute.

Jenkins Vangehn, who is now retired, spent nearly two decades working at the U.S. Embassy in Monrovia, where he started as one of the American mission’s locally employed staff, serving in the political and economic section. Vangehn’s long career at the U.S. Embassy spanned the tenures of several ambassadors, and included service during Liberia’s civil wars, which lasted 14 years and killed an estimated 250,000 people.

“Jenkins served the [Embassy in Monrovia for 17 years outside the time I was there,” said John Blaney, who was the ambassador from 2002 to 2005. “Many of these points were difficult and dangerous as well, and for those reasons alone, that qualifies him as a true U.S. hero of diplomacy.”

Joan Polaschik, the acting deputy director of the Foreign Service Institute, who hosted the virtual ceremony, said Jenkins took significant risk and “worked around the clock” to assist American citizens who found themselves trapped in their homes due to the fighting.

“Today, we are honored to recognize the selflessness and courage that Jenkins demonstrated during his country’s civil war years, and the all-out efforts he made to aid his country and support the U.S. mission in 2003,” Polaschik said. “At great risk to himself, Jenkins traveled under the cover of darkness to physically collect [Americans] and bring them to the embassy to be evacuated to safety. For this, and everything else that Jenkins has done to the American people, we are very grateful.”

Belinda Jackson Farrier, an acting deputy assistant secretary at the Bureau of African Affairs, said that at the time of Vangehn’s heroic actions, Liberia’s second civil war was in its beginning days and had already claimed the lives of more than 1,000 people.

“He courageously supported the mission through the most challenging of circumstances,” Farrier said. “Amid violent encounters and shortages of basic necessities, Jenkins also assisted in coordinating logistics for the embassy’s repatriation and evacuation efforts.”

But Vangehn’s heroic efforts were not exclusively reserved for Americans. He said it was Vangehn’s heroism and tenacity that convinced him to stay and negotiate to end the war. Blaney spoke about having to leave Ghana, where he was attending negotiations, because LURD and MODEL, the two rebel groups fighting President Charles Taylor’s government, were repeatedly breaking ceasefire agreements, therefore threatening prospects for a peaceful resolution, Blaney said.

“Jenkins played a crucial role in ending the 14-year civil war in Liberia, and really stabilizing much of West Africa,” Blaney said.

Blaney explained that as the rebels advanced to Monrovia, where 1 million people were trapped by the fighting, there was increasing pressure from Washington, D.C., to close down the U.S. Embassy. The ambassador said he found himself with the uphill task of trying to convince then President George W. Bush that – at a time when the United States was already engaged in two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – Liberia was important.

“We had to prevent the breakup of the Liberian nation state, and that would have ricocheted and cascaded into an entire failed region in much of west Africa, and it would have been an incubator for international terrorism,” Blaney said.

Convincing the Bush administration to keep the embassy in Monrovia open wasn’t easy, Blaney said, given that the embassy itself had been attached several times.

“We took thousands and thousands of incoming machine gun rounds, much of it from nearby battles, some of it directed, and very unfortunately and sadly, we did take casualties,” Blaney said. “This is precisely where our honoree comes in.”

Blaney said to convince the Bush administration to keep the embassy open, he had to have accurate information about all aspects of the conflict. Using knowledge from his Liberian background, Vangehn helped embassy officials gather intelligence they otherwise wouldn’t have. He said although there were American embassy officials who gathered information with Vangehn, as a Liberian, Vangehn could go “beyond the walls and gather and contribute to this type of granular information that I needed to decide what to do next.”

“Throughout all this, Jenkins worked nonstop and heroically to serve the embassy in Monrovia, but also to save his country,” Blaney said.

The information Vangehn gathered strengthened the case Blaney presented to Washington, D.C., in his desperate effort to keep the embassy open and ensured that the United States – the only country with a functioning embassy in Monrovia at the time – remained in the negotiations that led to the end of the war.

Vangehn said his desire to see and end of conflicts began in Yekepa, a small mining town in northeastern Liberia, where he was born and brought up. He was the oldest of six children. His father as a mining truck maintenance man, and his mother a trader who sold basic goods at the market.

“While growing up, I saw some of the things that shaped my opinions,” Vangehn said. “I saw my father held at gunpoint and severely beaten in front of my mom and my brothers because his only crime was he came from the same ethnic group as coup makers.”

While some might be tempted to seek revenge for the attack on their father, Vangehn decided to dedicate his life to finding diplomatic ways to resolved conflicts.

“I have always wanted everybody to have equality, everyone to be equal, and no one should suppress, repress, oppress anybody else,” he said.

Vangehn said when he worked at U.S. Embassy during the civil war years, there were several times he thought about leaving Liberia because it was too dangerous.

“I felt like it was not worth it because the warlords were not willing to lay down their weapons,” Vangehn said.

But he said that because of his “orientation” and “thought,” he felt like no Liberian should die because a few men wanted power for their own personal gain.

“So, I dug my heels in and said, ‘I’m going to be the sacrificial lamb to help save my country,’” he said.

For working with Americans to put pressure on President Taylor, Vangehn said he became the target of the regime and rebels. As he moved around Monrovia gathering information from he was threatened by some of the fighters who knew him.

“I was marked for elimination,” he said. “It was very treacherous, it was perilous, and it was dangerous.”

They invaded his home, but when they didn’t find him, they ransacked his house and killed his dogs. But that didn’t deter him. He lived in his office for three months and continued to do his work.

Vangehn remembered how worried he was in 2003 when it was almost certain that the Bush administration was going to shut down the embassy. He attended one meeting where Donald Rumsfeld, Bush’s secretary of defense, appeared determined to shut down the embassy. Rumsfeld ordered the three U.S. war ships stationed off the coast of Liberia to leave.

“I didn’t want a repeat of what happened in Rwanda, or in Bosnia because it was going to be a massive genocide,” Vangehn said. “So, I told myself, ‘I could leave with the Americans today, but what happens to my country? What happens to my people?’”

Instead of leaving, Vangehn said he decided to risk his life and work hard to help Blaney make the case for keeping an American presence in Liberia. He said he was so proud that his efforts led to the peaceful ending of the conflict and saved the lives of thousands of his countrymen and women.

“This is what brings immense satisfaction, immense joy to me.”

About Edwin Okong'o - Mshale Contributing Editor

Edwin Okong'o is a Mshale Contributing Editor. Formerly he was the newspaper's editor.