NEW YORK — On the day of their immigration interview, Catriona Dowling waited patiently at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) office in Denver, Colorado. At her side were her wife, Cathy Davis and their three young children.

NEW YORK — On the day of their immigration interview, Catriona Dowling waited patiently at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) office in Denver, Colorado. At her side were her wife, Cathy Davis and their three young children.

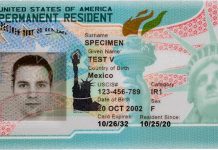

Dowling, 55, an American citizen, asked an immigration officer to approve her petition for a spousal visa for Davis, 42, an Irish national. Dowling was holding a copy of a statement by Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano, directing her agencies to extend immigration benefits to all binational same-sex couples, following the Supreme Court decision to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). A few minutes later, an immigration officer approved her request: Davis was issued a green card on July 3, becoming the first immigrant to receive a green card in a binational same-sex marriage in the United States.

At that moment, Dowling said, she cried.

“It was a very special day and I was overwhelmed with emotion,” Dowling said in a phone interview from their home in Boulder. “We’re just excited and relieved —and now we can make plans for our future with no disruptions.”

After the Supreme Court struck down DOMA nearly three weeks ago, marriage-based green card approvals for binational same-sex couples are beginning to be issued. For these couples, the Supreme Court ruling marks a turning point – the end of their immigration limbo and ability for their families to remain intact.

Madeleine Sumption, senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, said that these green card approvals mean that federal benefits are being extended immediately to same-sex married couples, including immigration benefits.

“Immediate relatives, such as a spouse, have special priority and they do not have a waiting time [for a visa number]. They also do not have a global cap or limit in the number of visas each year,” said Sumption. “So it does not really affect the backlogs in other immigration visa categories.”

While the number of green card holders may rise, as more and more binational same-sex married couples are expected to apply, not to mention those who are already in line, Sumption says “it would be [a] relatively small… overall increase in the next 10 years.”

Who are these binational same-sex married couples?

According to a 2001 report by the Williams Institute of UCLA School of Law, there were an estimated 28,500 binational same-sex couples in which one partner is a U.S. citizen and the other is not.

Among noncitizens in binational couples, 45 percent of them are Latino; 36 percent white; 3 percent black; and 14 percent Asian and Pacific Islander.

Like Dowling and Davis, most of these couples have found themselves in immigration limbo — whether the non-citizen spouse’s visa is about to expire or facing deportation — and filing their green card applications even months or years prior to DOMA’s historic repeal is their last resort to stay together in the country.

“We were running out of options as far as keeping our family together,” said Dowling. “So our lawyer advised us to get married and submit our application. We thought, ‘well, let’s do it.’ We were going to get married, anyway.”

Derek Tripp, an immigration attorney and project associate of the DOMA Project, the Los Angeles-based organization that also handled Davis’ immigration case, said that binational same-sex couples somehow face a similar immigration predicament, desperately doing what they can do to stay together in the United States.

And the foreign spouse, at least in cases that they are currently handling, have come from different parts of the world, including Ecuador, the Philippines, Indonesia and Trinidad and Tobago, to name a few.

“We are now expecting to receive more green card approval for same-sex married couples,” said Tripp. “The processing time would be no different from any other married couples, but we want to make sure that the USCIS fairly and expeditiously handle their [same-sex couples] cases.”

Since 2010, Tripp said that his organization has filed about 100 applications for binational same-sex married couples — and most of them were repeatedly denied due to DOMA’s definition of marriage as between one man and one woman.

However, they appealed through the USCIS administrative body, asking it to hold off on their immigration cases until the Supreme Court handed down its decision.

“We have advocated to have access immediately, and right now we don’t see any delays from immigration officials,” Tripp said. “These green card approvals can be considered the closure of a chapter for many same-sex couples who struggled under DOMA. It’s time for them to move on with their lives.”

Under the current U.S. immigration law, a U.S. citizen may petition for permanent residence for a non-citizen spouse and expedited citizenship for a resident.

A permanent resident spouse may also obtain permanent residence status for a spouse with a non-immigrant status such as those who are on a student, tourist or worker’s visa.

Fighting for green card, keeping family together

In 2006, Dowling and Davis met at a mountain-climbing trip in the Himalayas. Their romance blossomed instantly, but after the trip Dowling had to go back to Colorado and Davis to Dublin.

They continued a long-distance relationship and visited each other as often as they could.

Two years later, Davis, who is a nurse, was hired in a hospital in San Antonio, Texas. She came back to the United States on a work visa and Dowling, an I.T. executive, relocated to Texas so they can live together.

Dowling and Davis together adopted three children. They brought home their son, Cian, now 6, from Guatemala in 2007. Their two daughters, Mardoche and Angelina, now 11 and 9, respectively, came home with them from Haiti in 2010, after a massive earthquake hit the country.

But, in 2012, when Davis tried to extend her visa based on a job promotion, it was denied. That decision meant that Davis had only two options: overstay her visa in the United States or leave behind Dowling and their children.

“We definitely thought about moving to another country,” said Dowling. “We didn’t exactly know [which country], but we definitely considered it,” she added. Ireland was out of the question: it does not recognize same-sex marriage.

Undeterred to break UP their family, Dowling and Davis decided to fight their case. They packed up and moved back to Colorado.

On June 12, 2012, they got married in Bluffs, Iowa – the state recognizes gay marriage — even though it was unclear if under federal immigration law, they could stay together.

On the day that their entire family was at USCIS for the interview, and Davis was given a green card, Dowling had never felt victorious before in her life.

“This is not just a same-sex couple issue—it is really a family issue. It is that simple, and we want everyone to understand,” Dowling said. “Now we are ready to decorate our kids’ room and look forward to be at their soccer games in the fall.”

About New America Media

New America Media is the country's first and largest national collaboration and advocate of 2000 ethnic news organizations.