Mental health providers of African descent should take it upon themselves to create culturally appropriate remedies to a crisis that has been exacerbated by effects of the coronavirus pandemic, experts said in a recent summit.

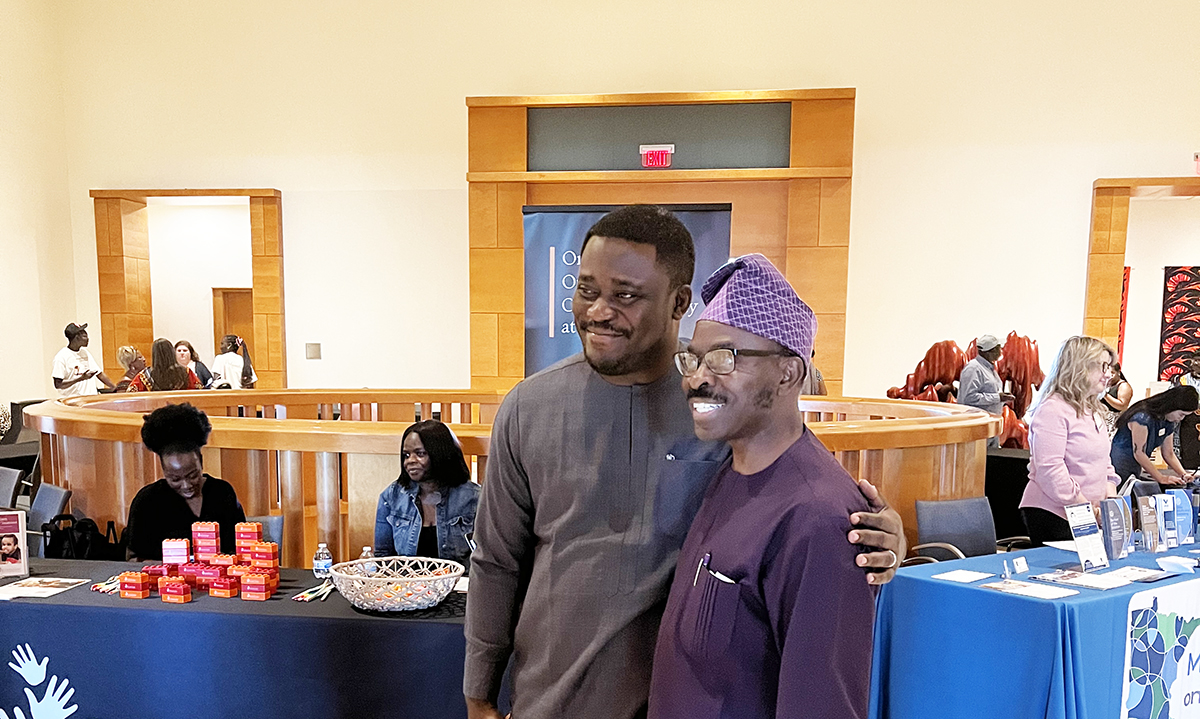

The experts spoke recently at the African Mental Health Summit, which returned to Minnesota’s Twin Cities to continue a conversation that began nearly a decade ago to explore how best to tackle mental health issues in African communities. The two-day conference, which was in its ninth year, was themed “Mental Health Inequities Post Pandemic: Building a Cultural Ecosystem of Well-Being” and began on July 14 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and ended in St. Paul at the Wilder Foundation.

The theme color for this year’s summit was purple, which represents creativity, energy, and spirituality, according to Nigerian-born Dr. Richard Oni, who founded the summit eight years ago. Oni said that the coronavirus pandemic indiscriminately took a high toll on African communities, creating an urgent need mental health services.

“Everyone, regardless of tribe, needs good mental health,” Oni said, who is also the executive director of Progressive Individual Resources, Inc., a St. Paul-based organization that trains service agencies how to serve children and families from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Although mental health is an uncomfortable subject worldwide, it’s even more so in African communities, where people dealing with psychological illnesses are often ostracized. Efforts to provided care are further complicated by a lack of funding. Most African countries allocate less than 1% of their annual budgets toward mental health care, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The lack of investment means that more than 80% of Africans struggle with mental health issues like depression without treatment.

The coronavirus pandemic “triggered something in us,” causing people to become more irritable, agitated, and frustrated, said Andre Dukes, the vice president of family and community impact programs at Northside Achievement Zone (NAZ), a nonprofit that advocates for education as a means to eradicating generational poverty in North Minneapolis’s communities of color.

“The compounded effects of racial injustice and political upheaval during quarantine caused us to see the world through a dark lens,” Dukes said.

In his keynote address, Dr. Bayo Akómoláfé, a clinical psychologist and a scholar who is also a fellow at the Othering and Belonging Institute at University of California, Berkeley, said it was important to construct Afro-centered wellness practices to deal with the setbacks of the pandemic.

“We could not have anticipated that after 30, 40, 50 years of doing climate justice work – of trying to get everyone to slow down – it was a tiny, seemingly infinitesimal critter of a virus that stole into our economy and sent everyone home invisible,” Akómoláfé said.

A study published in 2001 in the South African Journal of Psychiatry, found that isolation and quarantine associated with COVID-19 lockdowns, along with the grief that followed the loss of loved ones, adversely impacted the phycological wellbeing of many Africans. As of July 19, the WHO estimated that there were 9.5 million cases of COVID-19 in Africa, leading to more than 256,000 deaths.

Dr. BraVada Garrett-Akinsanya, a licensed clinical psychologist and executive director of African American Child Wellness Institute Inc., said when addressing mental health issues, it is also important to acknowledge the generational trauma that dates to slavery, and the racism that is still exists today.

“People will try to tell you they didn’t own any slaves, yet they are comfortable with the effects of it,” she said.

Akinsanya also spoke about how microaggressions – subtle remarks rooted in stereotypes – can affect an individual’s self-esteem. According to a study published in Harvard Business Review, people subjected to microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of negative emotions. The study also found that Black individuals experienced microaggressions at significantly higher rates, which impacts their mental health and performance at work.

The summit also reiterated the importance of making efforts to raise awareness and correct the problematic attitudes many in the African and African American communities possess towards mental health. Oni, the founder, talked about destigmatizing the conversation around mental health and wellness in the African community, adding that mental health is just as important as physical health.

“We should have a paradigm shift,” Oni said.

Victor Obisakin, a member of the Nigerian community, fought tears as he explained why he attended the summit. He said that he had recently lost his sister, who struggled with mental illness.

“I started crying back there,” Obisakin said, pointing to where he had been sitting. “I wish she was here to see that there’s hope in the African community.”

Obisakin agreed with the experts that methods of treating mental illness in the African community should be more culturally specific. For example, African Americans and African immigrants share skin color, but there are cultural differences between them that mental health providers often miss when treating patients, he said.

“We need to decolonize the system and the tools used to diagnose our people,” Obisakin said. “When you have the wrong people with the wrong tools, that’s [when] you have problems.”

Dukes, the NAZ vice president, said he saw those differences in culture when he traveled to Senegal, where he noticed a deep sense of community that was absent in his neighborhood in the United States. People in Senegal, he said, had a spirit of togetherness, and a culture of being responsible for each other. He said the United States could borrow from such cultures to create a stronger mental health support system.

“That culture of ‘What I have, is also yours’ is the ecosystem we all need to remain mentally healthy and spiritually whole,” Dukes said.

Ultimately, it is mental health providers of African descent who can come up with viable solutions that are tailored to their unique cultures. Akómoláfé, the Berkeley fellow, said African countries needed not just monetary funding but also implementation of creative strategies to address what he said was a mental health care crisis. He gave an example of Nigeria, his country of birth, which when he began his Ph.D. had only three functionals psychiatric hospitals to serve a population of 200 million people.

“The government was trying to address this crisis by pumping more money into the hospitals, but somehow [it didn’t] translate to real reforms,” he said.

Another challenge African communities must address, according to Akinsanya, is the shortage of Black experts in the mental health profession. In the United States, for example, a mere 2% of members of American Psychological Association identify as Black or African American, according to the professional group, creating concern that most providers lack the cultural competence required to guarantee adequate care.

“A lot of us are trained by white people,” Akinsanya said. “A middle-aged white man from [a tiny Minnesotan town, for example,] sets the standards for culturally responsive mental health care. That is our problem.”